Let’s take a tour through ScreenFloat and see how it can power up your screenshots, too.

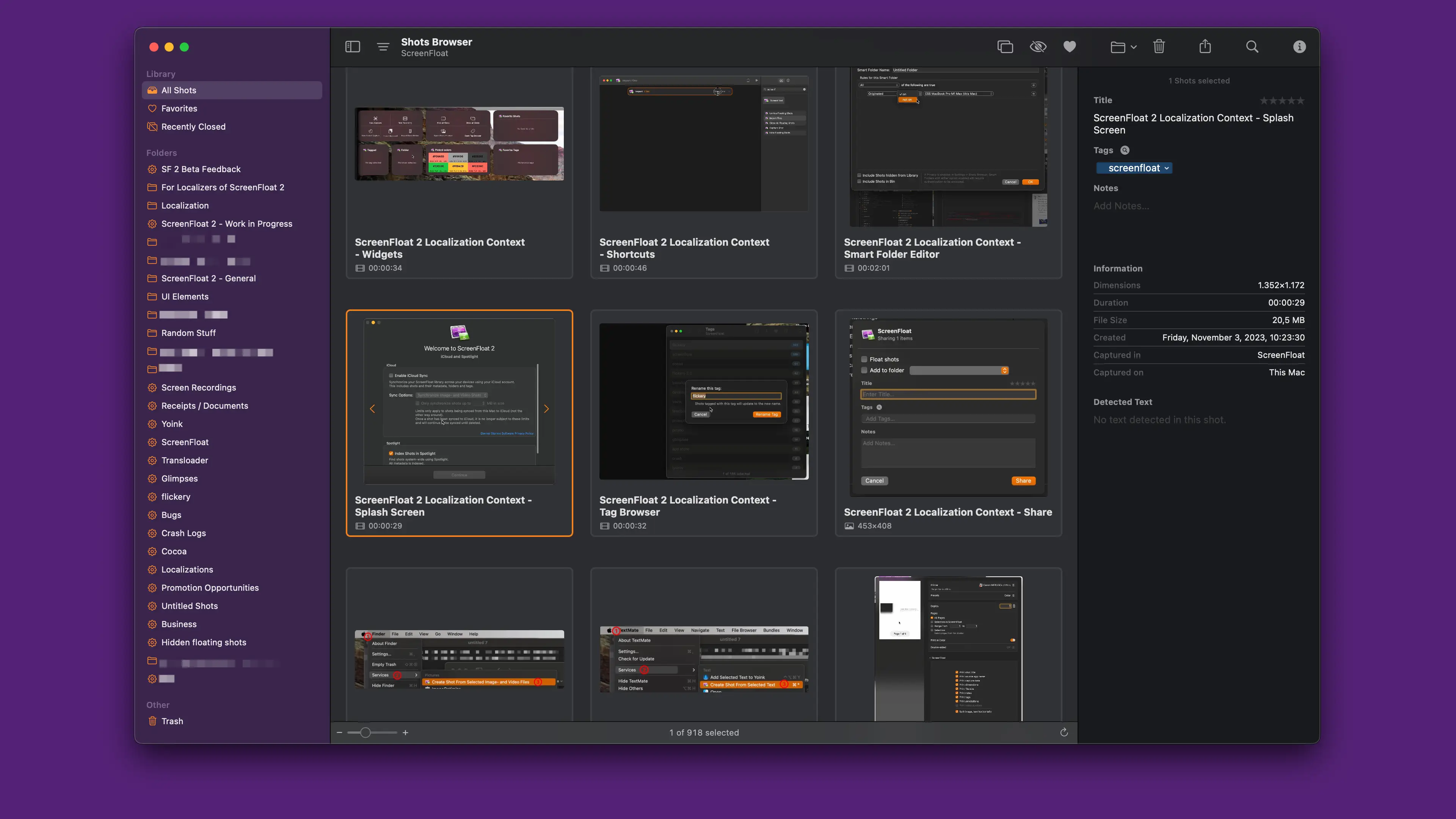

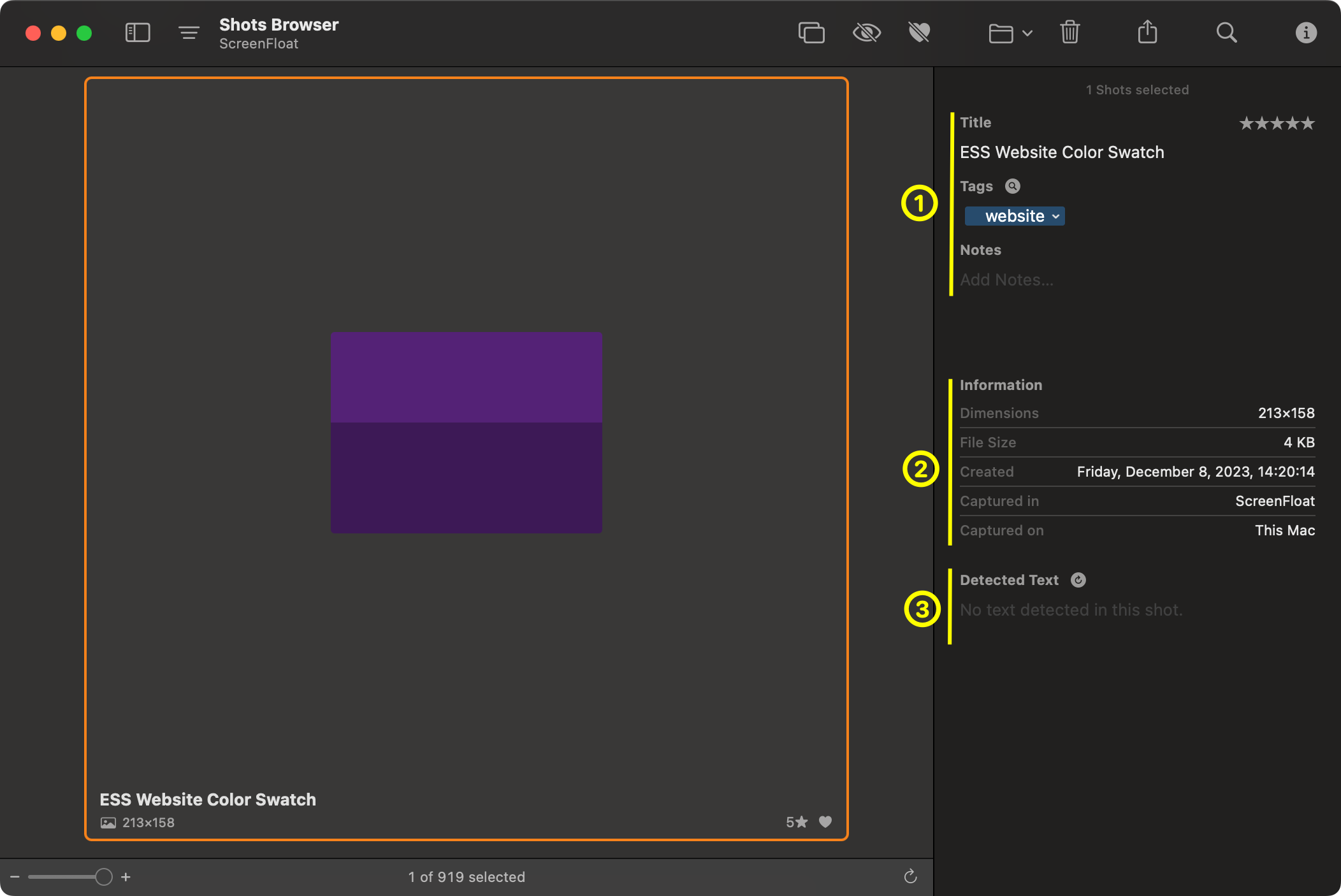

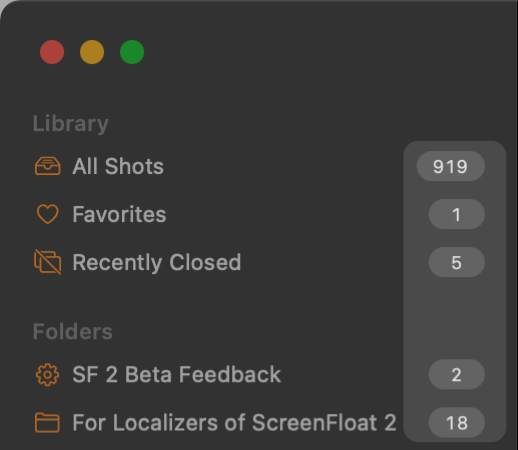

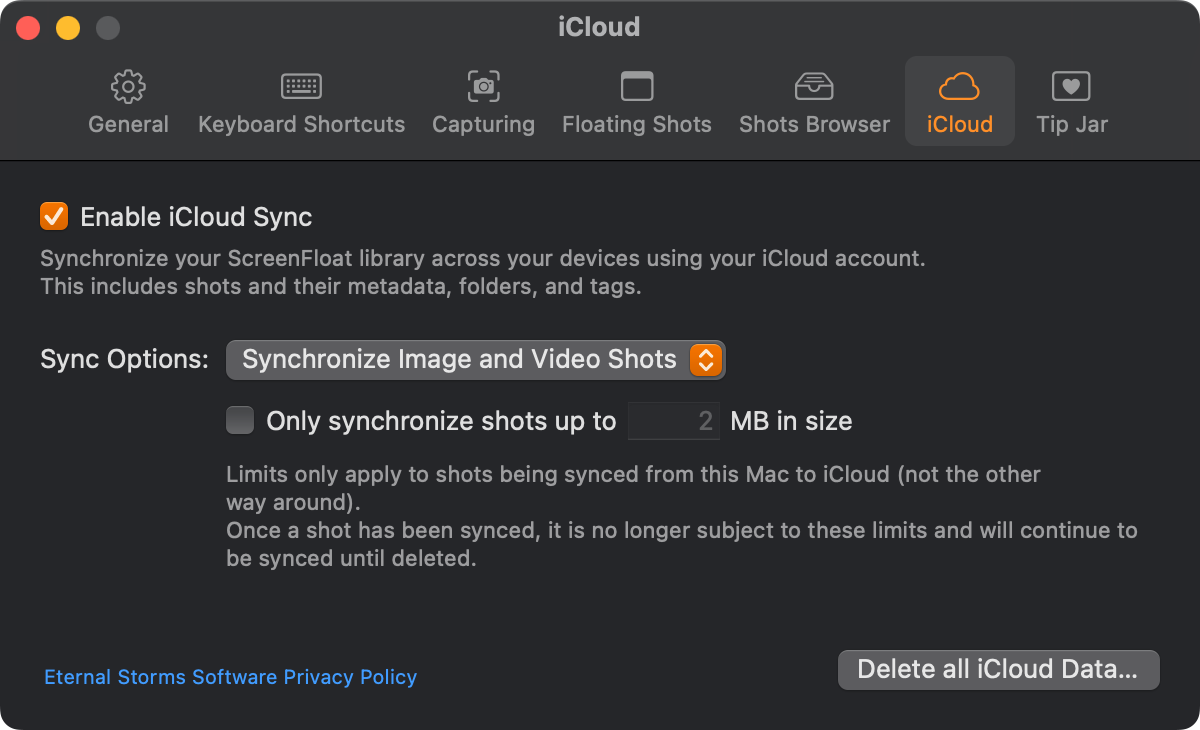

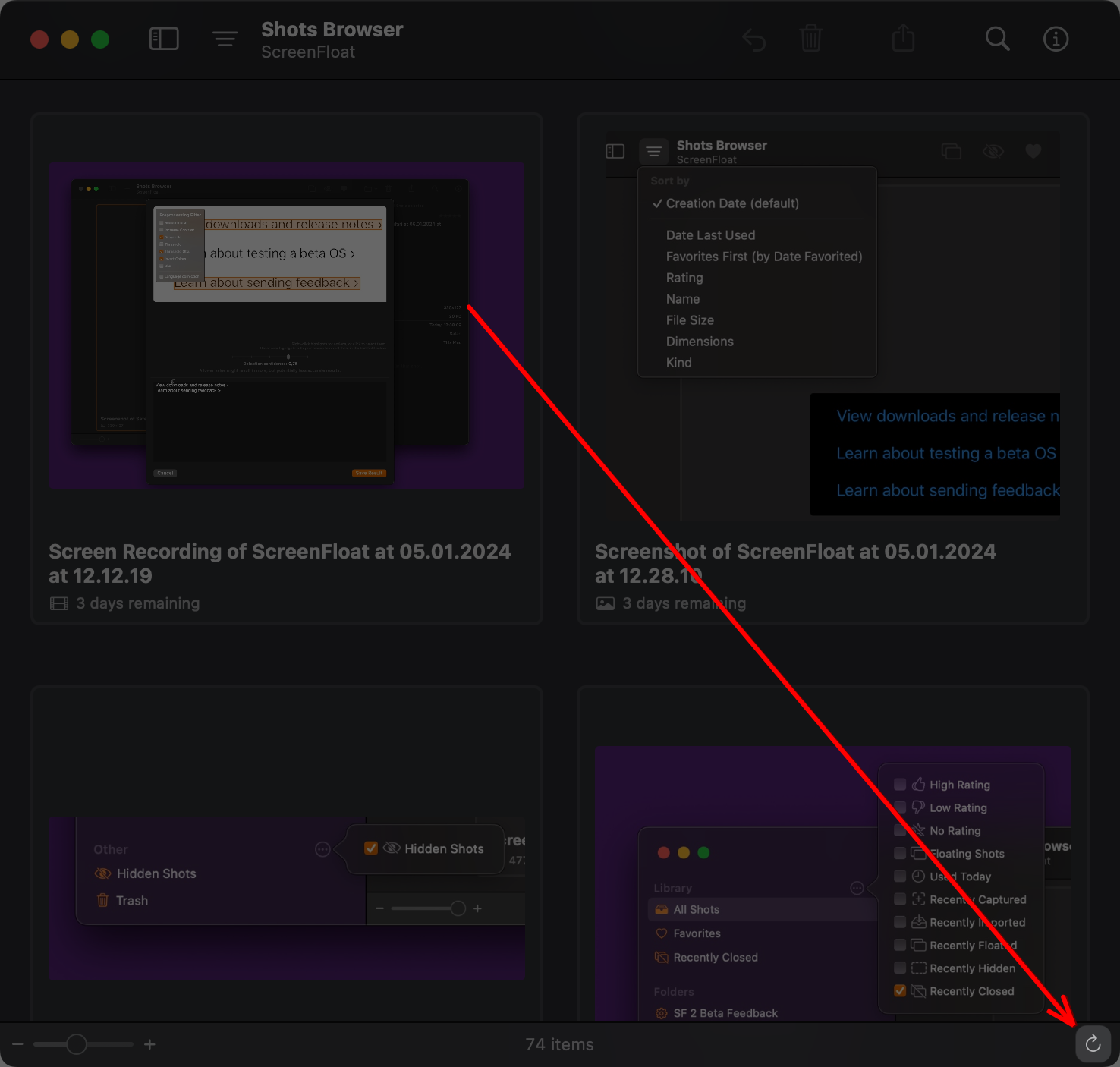

ScreenFloat powers up your screenshots by allowing you to take screenshots and recordings that float above everything else, keeping certain information always in sight. Its Shots Browser stores your shots and helps you organize, name, tag, rate, favorite and find them. Everything syncs across your Macs.

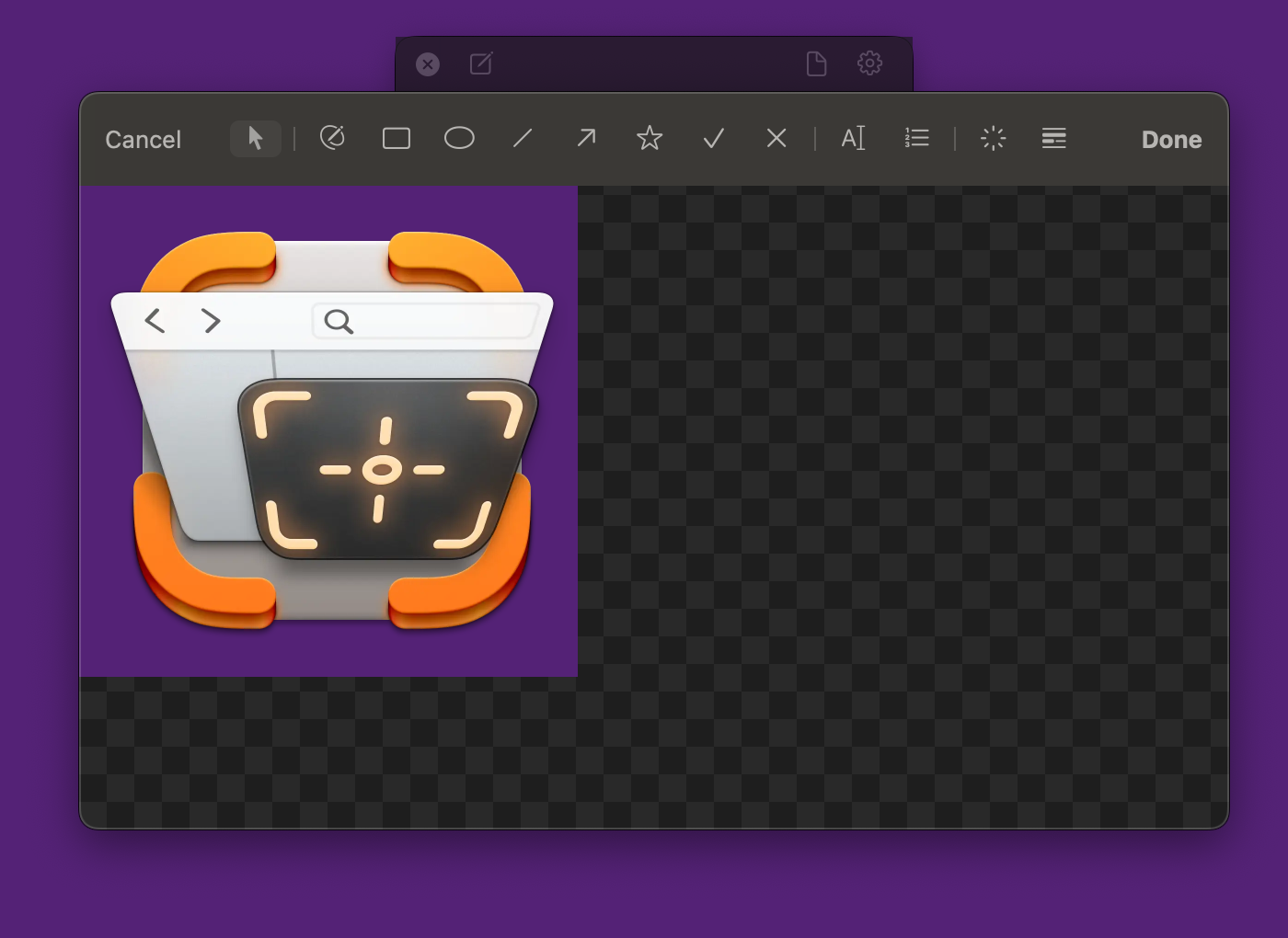

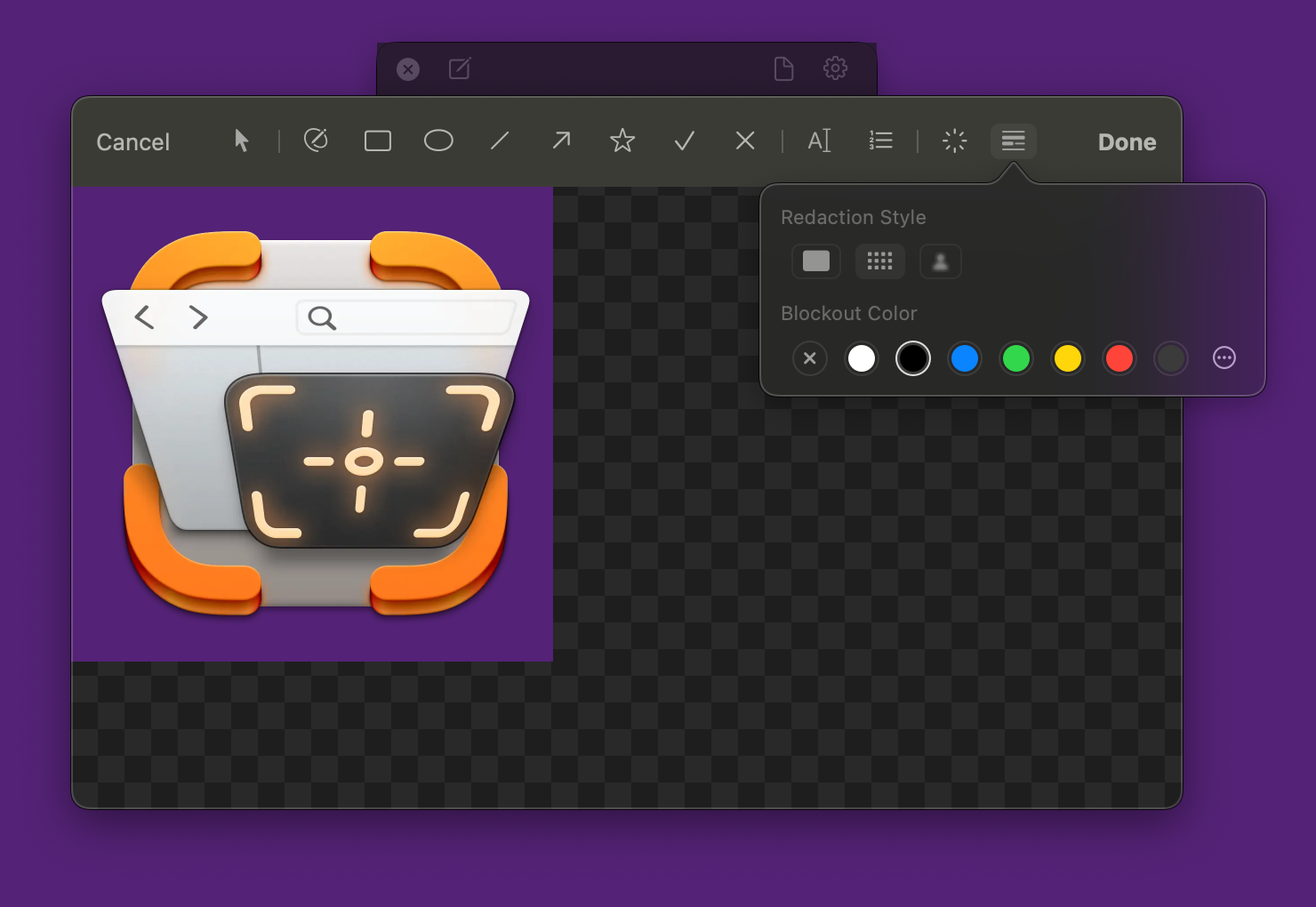

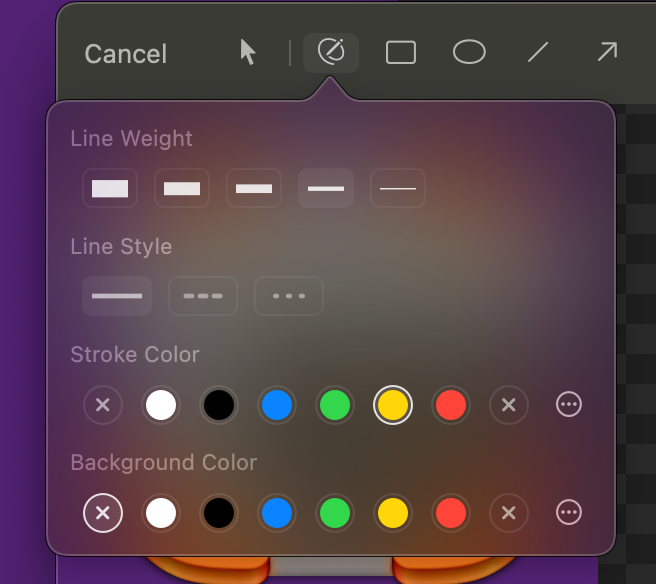

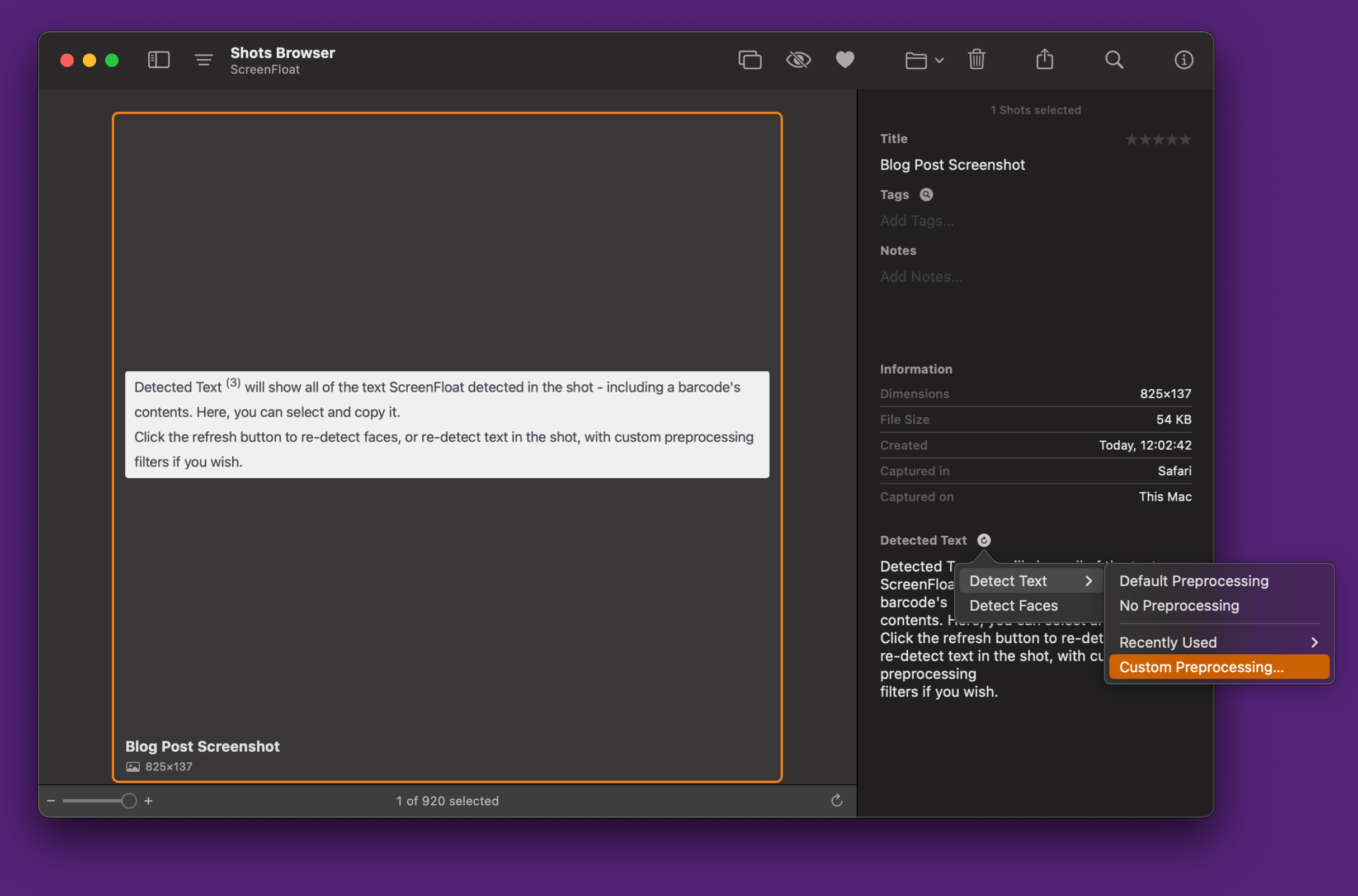

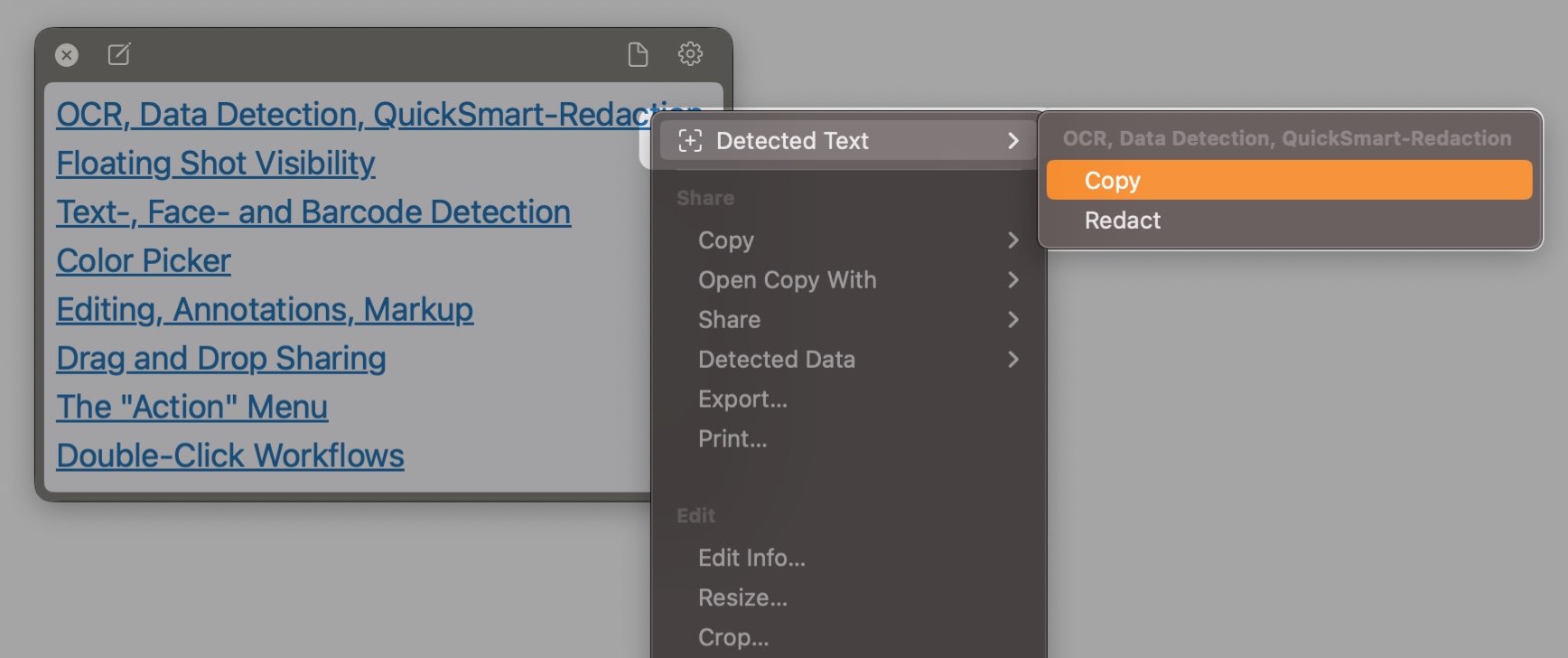

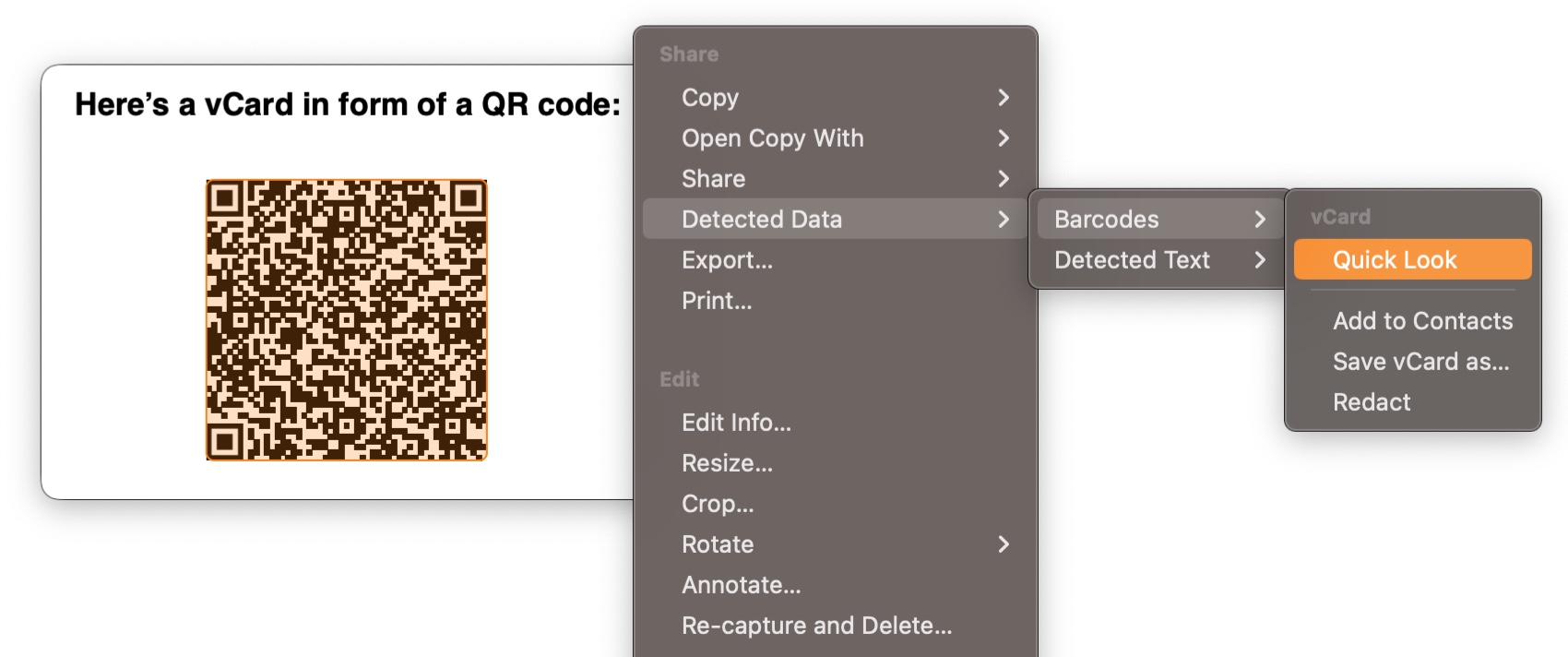

Extract, view and copy detected text, faces and barcodes. Edit, annotate, markup and redact your shots effortlessly and non-destructively. Pick colors any time. And more.

Posts in this Series

Part VII – Widgets, Siri Shortcuts, AppleScript, Workflows, Spotlight

ScreenFloat integrates perfectly with macOS, so you can easily and comfortably capture and access your shots any way you want to. Read on to learn how.

Table of Contents

Widgets

ScreenFloat offers you a number of widgets, ranging from quick access to capturing your screen and managing your floating shots, over quickly accessing your shots, to folders and picked colors.

Command and Control

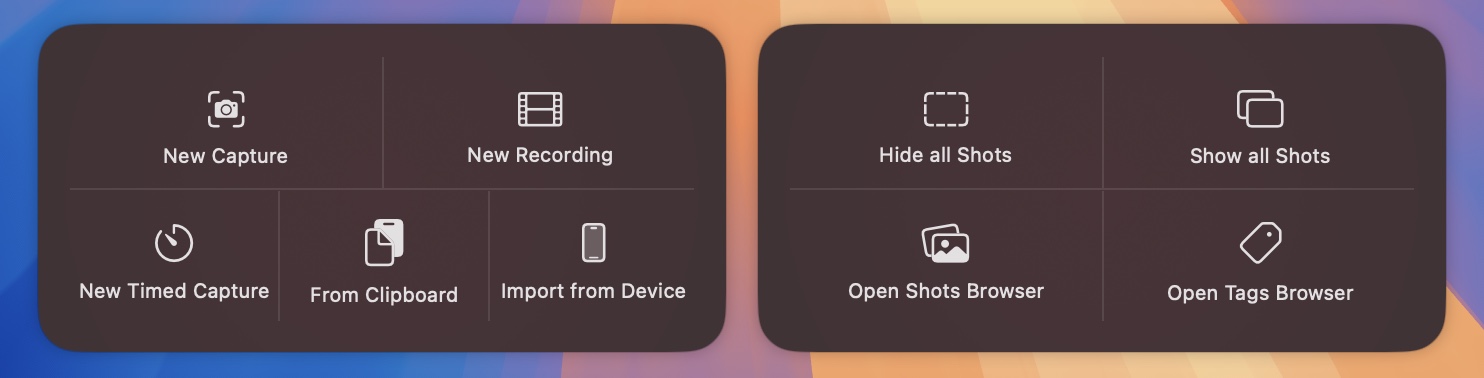

These widgets allow you to control all aspects of ScreenFloat – capture new shots and recordings, manage your floating shots and open the Shots- and Tags Browser.

These might be especially useful placed on your Desktop, if you’re on macOS 14 Sonoma or newer.

Quick Access to Shots

With “Shot”-family of widgets, you get quick access to:

- Favorite Shots

- Recently Captured Shots

- Shots in a specific folder

- Recently closed floating shots

- Shots tagged with a specific tag

Clicking a shot will reveal it in the Shots Browser.

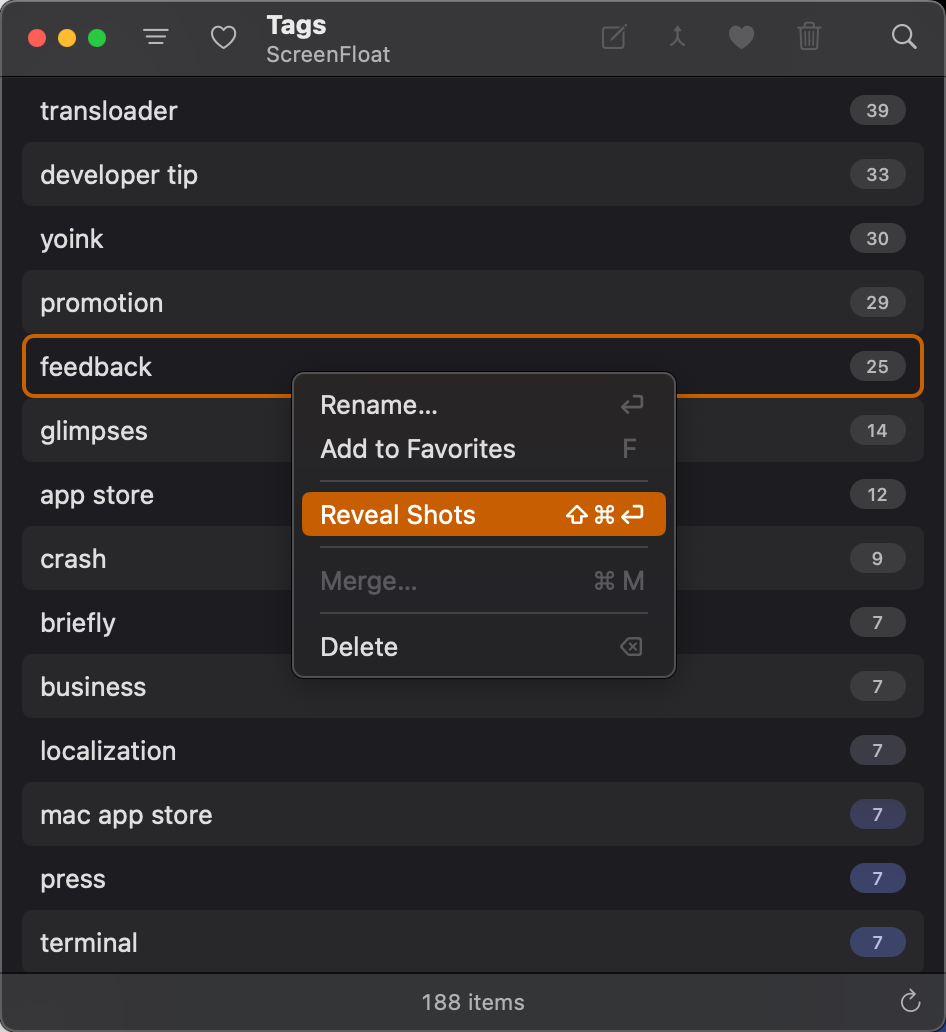

Tags and Colors

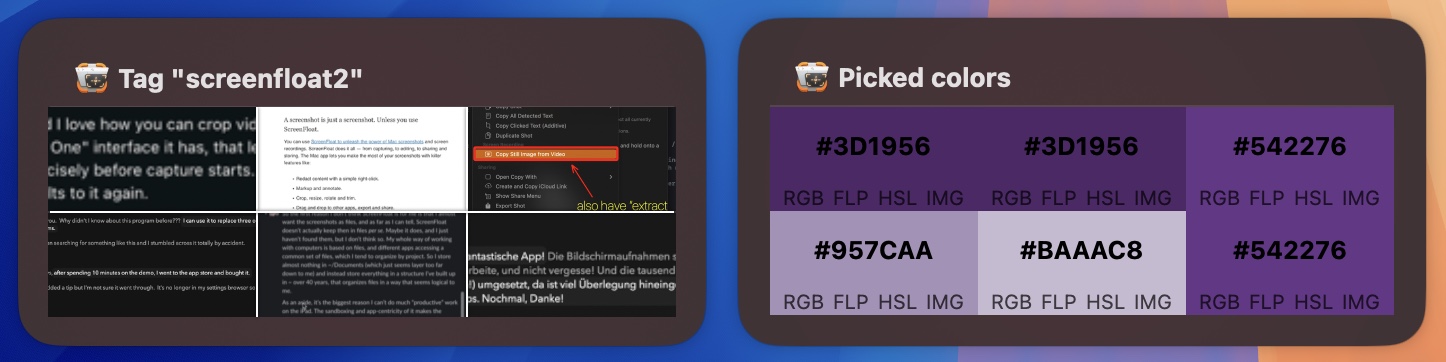

And lastly, you can have quick access to your favorite tags, and recently picked colors.

Clicking a tag in the Favorite Tags widget will reveal it in the Tags Browser.

The color widget allows you to copy a color’s hex-, rgb-, float- or hsl values, or a sample color image.

Siri Shortcuts

To integrate capturing your screen into a Shortcut, ScreenFloat comes with a couple of useful Shortcuts to help you do that.

Here are ScreenFloat’s shortcuts available to you:

Capture Shot

Allows you to automate capturing a screenshot, timed screenshot, or screen recording.

Options include:

- Float shot

whether to float the new shot after capture or not - Title

- Notes

- Tags

- Recapture previous area

if, instead of starting a new capture, the last known screen area should be preselected for the capture - Add to Folder

select a folder to add the newly created shot to - After Capture

what should happen right after capture. Current options are: do nothing, Annotate Shot, Crop Shot, Resize Shot, Reduce resolution, Trim Recording, Cut Recording, Create iCloud Link, Create ImageKit Link, Create Cloudinary Link

New Shot from Clipboard

Create a new shot from the contents of your clipboard: images, videos, or text.

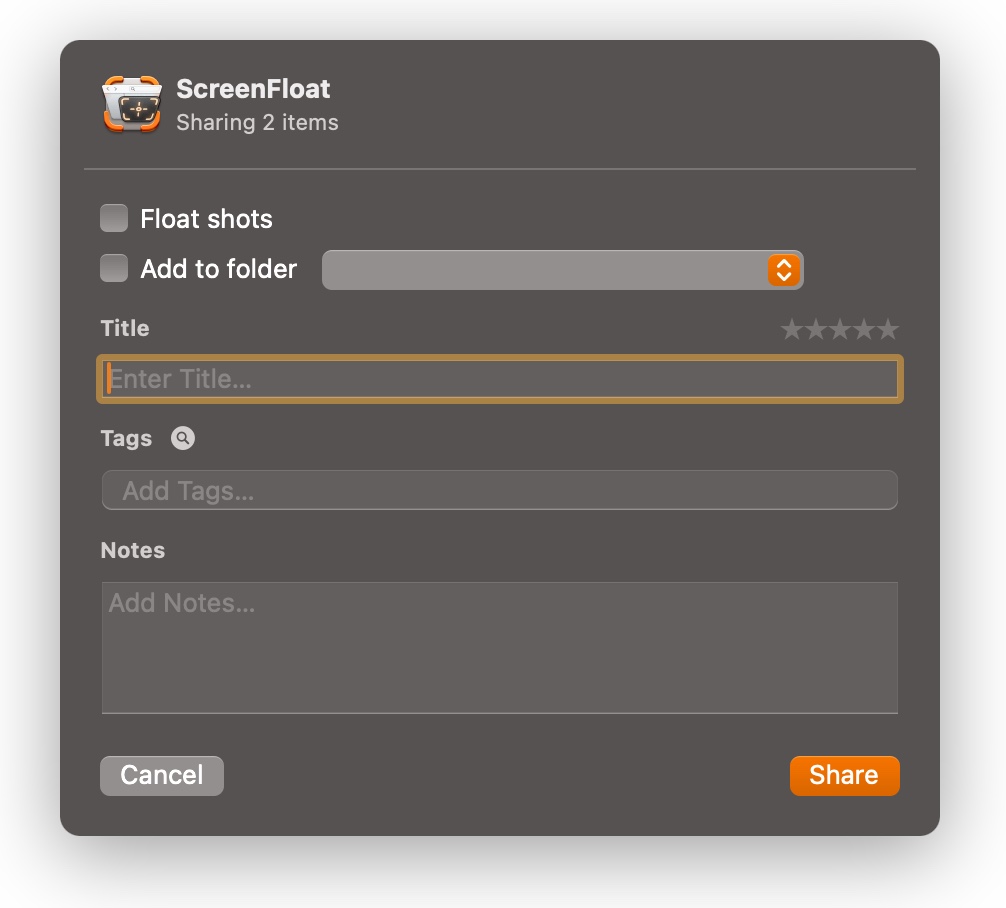

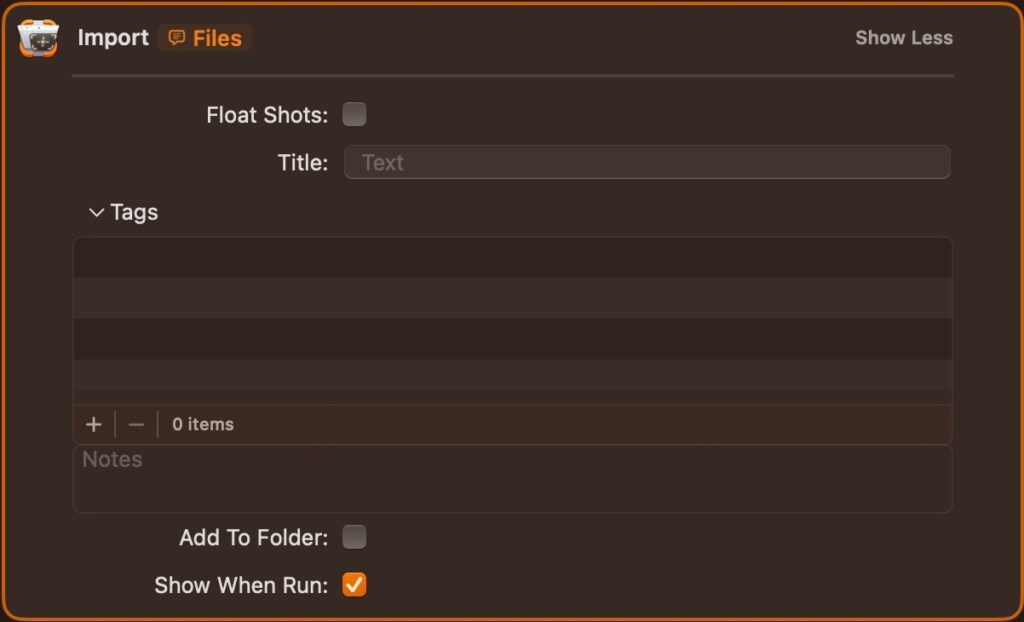

Import Files

Import specific image or video files into ScreenFloat, with the same options as Capture Shot.

Hide / Unhide Floating Shots, Close All Floating Shots

Manage your floating shots’ visibility.

URL Scheme

ScreenFloat’s URL scheme gives you access to all of ScreenFloat’s capturing functionality from the comfort of a URL, allowing you to automate captures in your own style.

For all the available options and instructions, please click here.

AppleScript

ScreenFloat allows you to run Application Scripts (AppleScripts that reside in a special folder on your Mac) as a double-click workflow, passing in a copy of the double-clicked shot, along with a couple of other parameters.

For all the details and instructions, click here.

This opens up a wide possibility of options to you, like creating your own Link Share service, uploading the shot to your server and copying a link to it to your clipboard, or direct-pasting shots into the active app’s window.

As coincidence has it, here are, coincidentally, two sample scripts that allow you to do exactly that.

- Sample AppleScript to upload the double-clicked Shot to FTP server and copy link to pasteboard (direct download)

Uses the passed-in fileURL and uploads it to your FTP server, copying the link to it to your clipboard afterwards - Sample AppleScript to direct-paste the double-clicked Shot into the active app’s active window (direct download)

Emulates a command-v keypress for the active app. Best used together with a Copy Shot double-click action so you don’t have to copy the fileURL in the script.

You can also run Shortcuts with your shots as a double-click action. Read on for more information on both AppleScripts and Shortcuts as Double-Click actions.

Double-Click Workflows

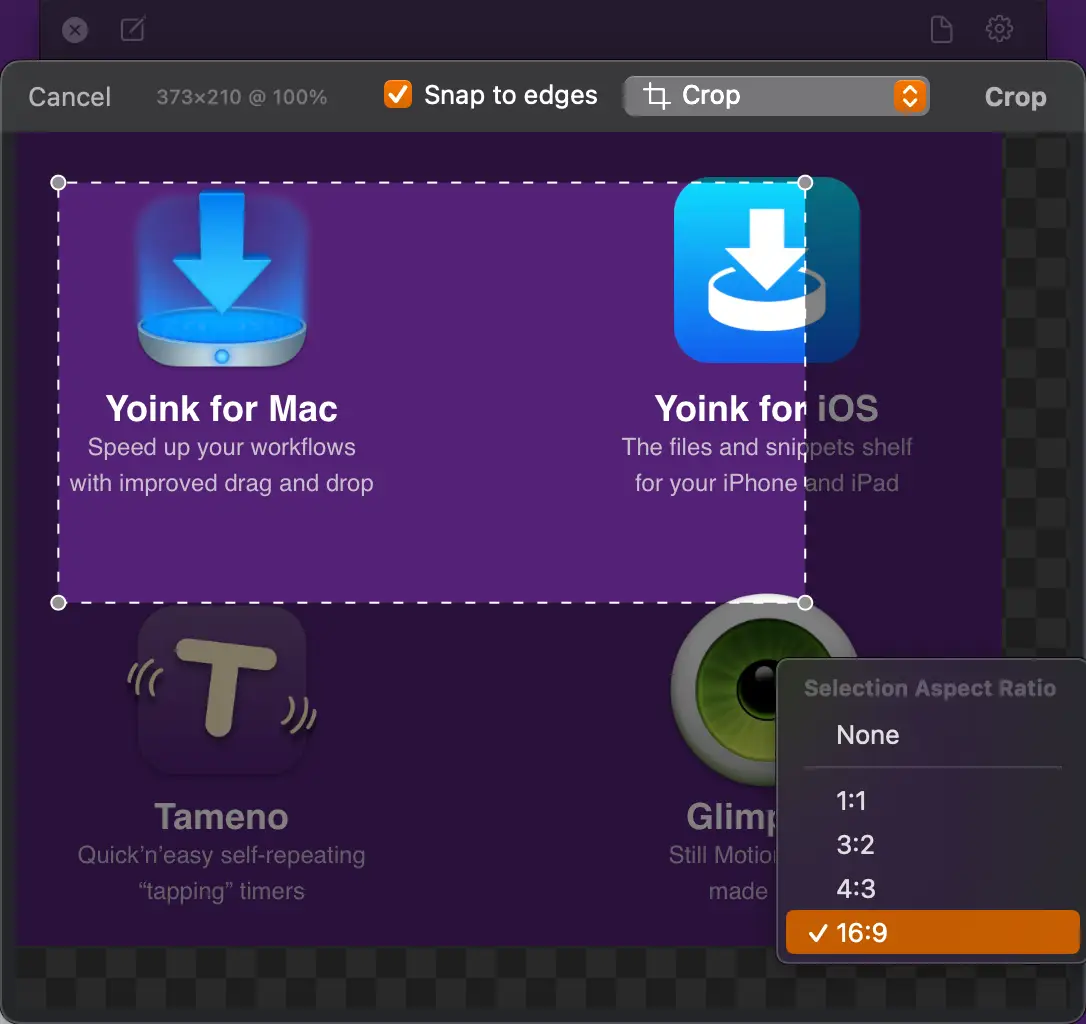

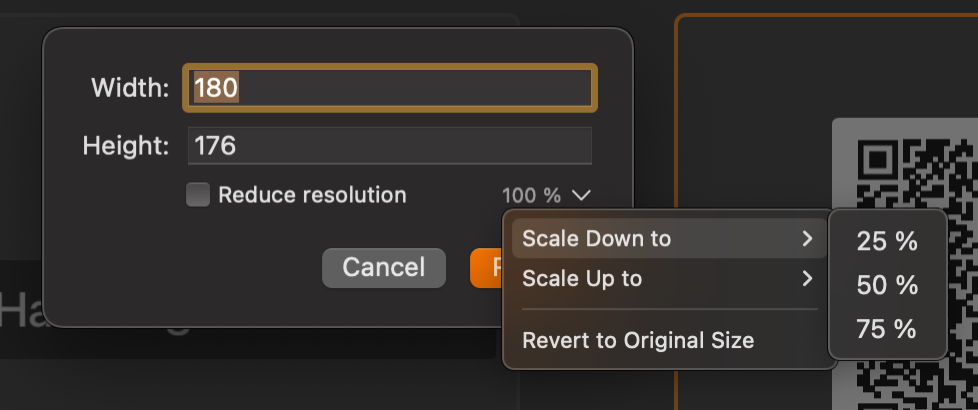

From time to time, you’ll find yourself doing something over and over again, like resize an image before you send it in an email, or crop an image before you annotate it, or duplicate a screen recording before you remove its audio tracks.

ScreenFloat speeds that up by providing customizable double-click workflows for your floating shots.

Setting up Double-Click Workflows

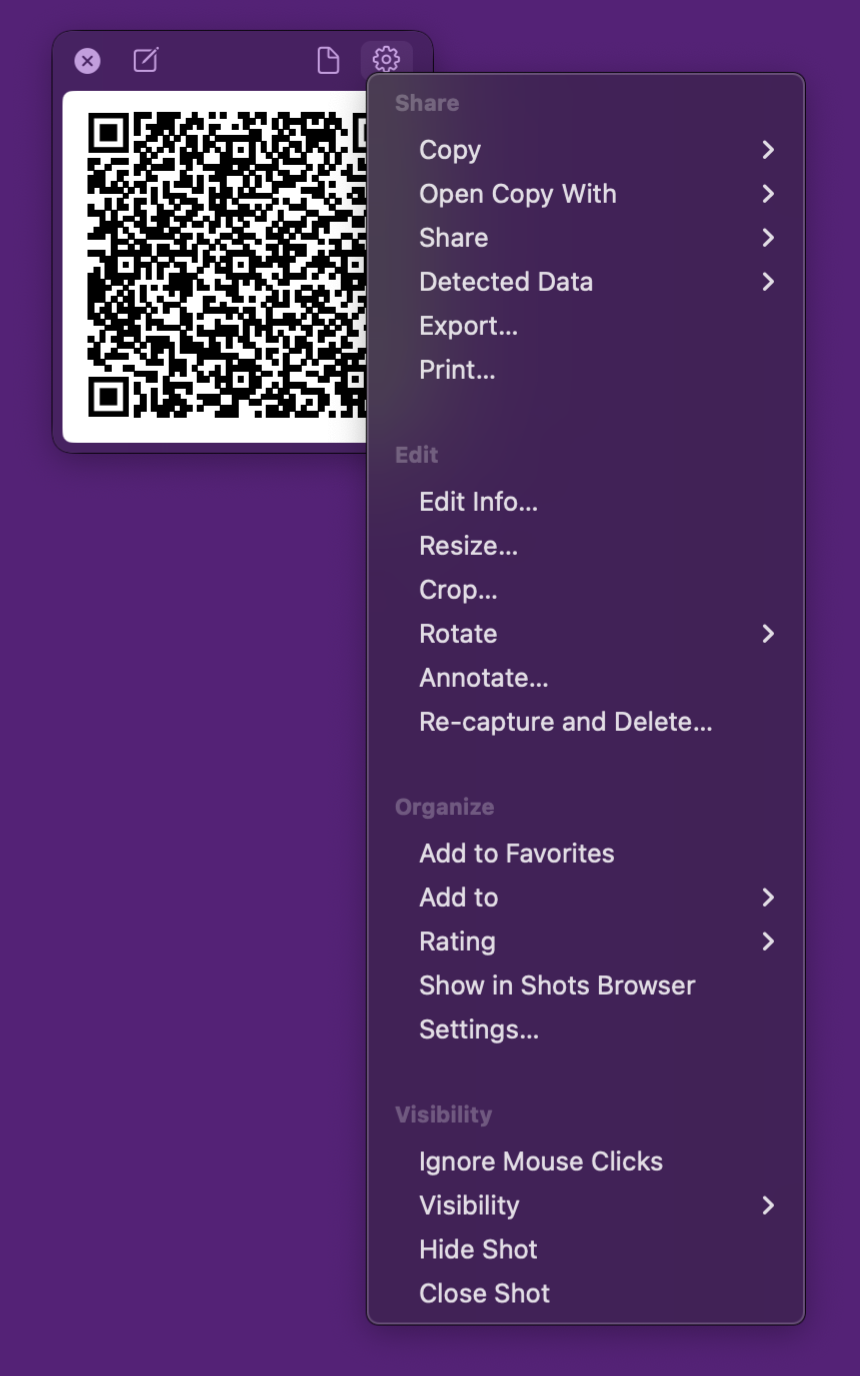

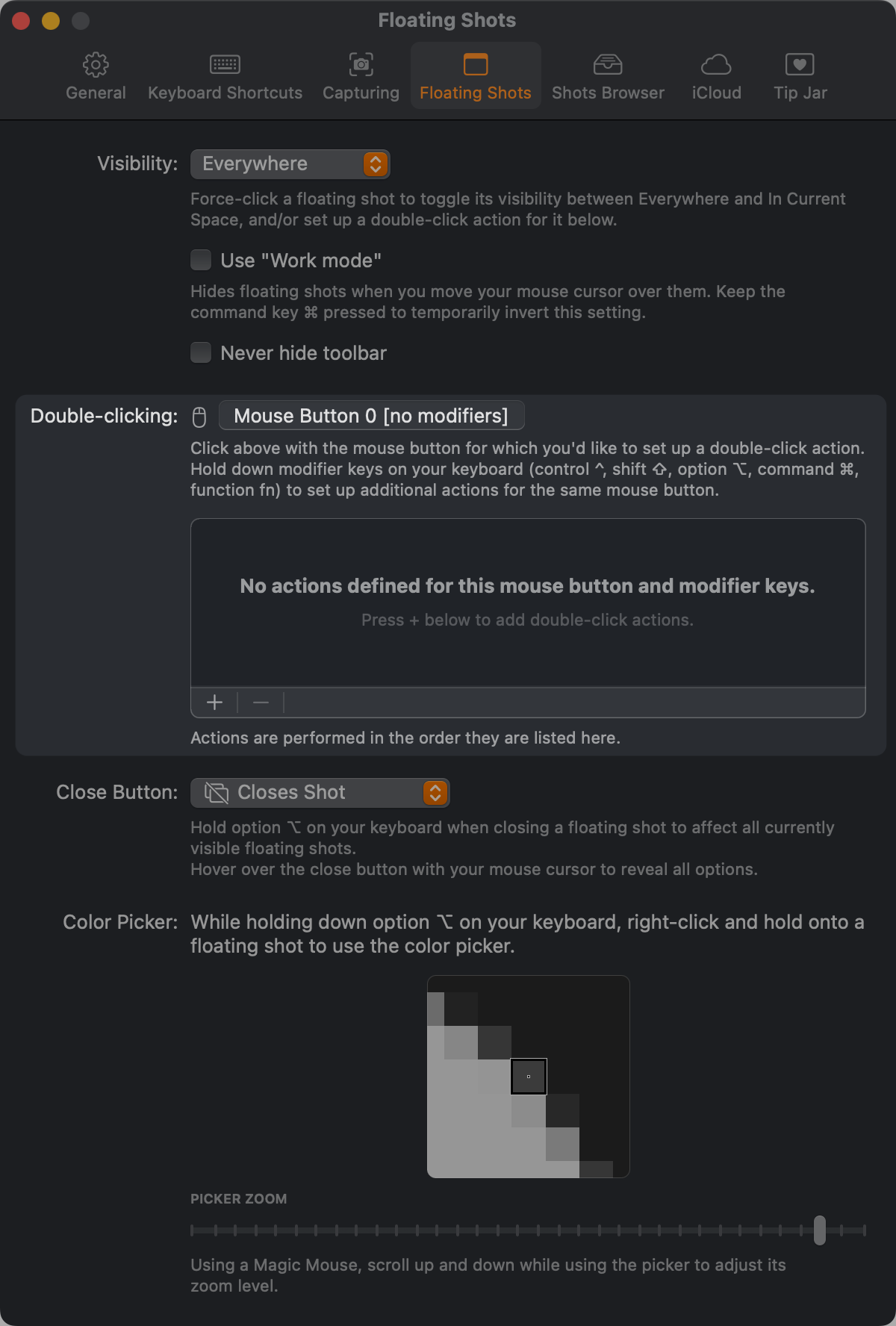

Double-Click workflows are set up in ScreenFloat’s settings. You can reach them by clicking on ScreenFloat’s menu bar icon in the right portion of your menu bar; or by right-clicking any floating shot; or by pressing command (⌘) – , in the Shots Browser. Select Floating Shots, and you’ll be ready to get going:

You can set up double-click workflows for different mouse buttons, and different modifier keys on your keyboard (command (⌘), option (⌥), control (^), shift (⇧) and fn).

For instance, you can set up workflows for your left mouse button with no modifier keys pressed (a simple double-click onto the floating shot), or your middle mouse button with command (⌘) and shift (⇧) pressed.

This allows you to set up not just one, but multiple double-click workflows, tailored to different situations or requirements.

To add a double-click action to a workflow, hold down the modifier keys of your choice (or none) and press the mouse button area at the top of the list with the desired mouse button. Then press the + button at the bottom of the list to select actions you’d like to perform on the floating shot you double-click.

The – button allows you to remove selected actions from the current workflow, remove all actions from the current workflow, or completely reset all your double-click workflows.

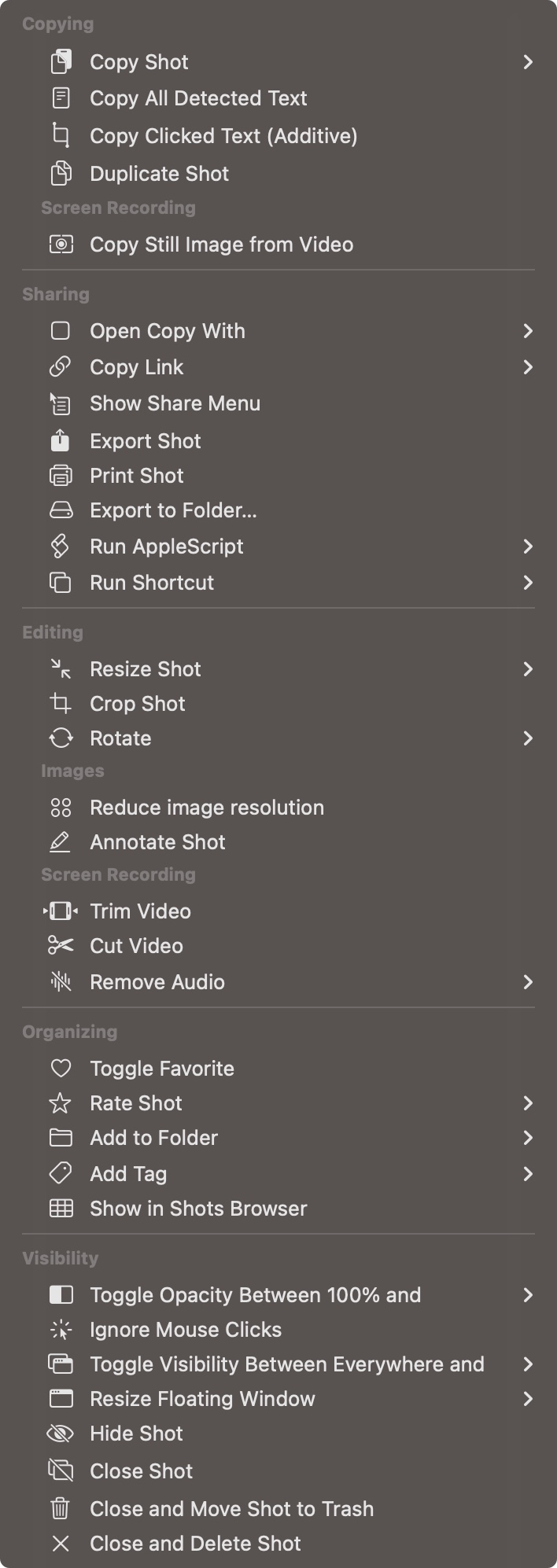

Available Actions

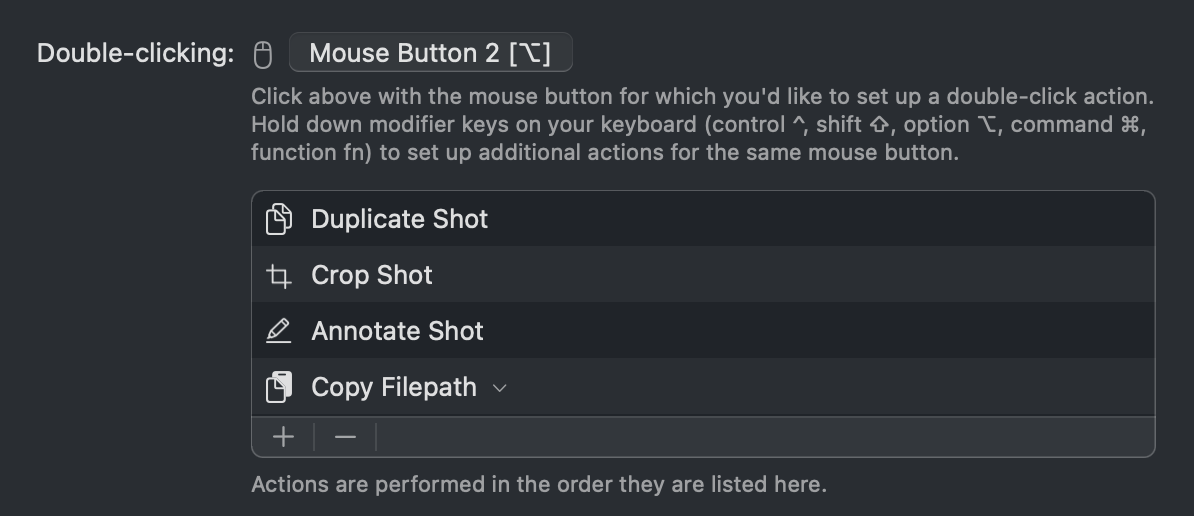

Actions in a workflow are performed in the order they appear in the list when you add them.

This order is more or less pre-defined and cannot be changed: for instance, the Duplicate Shot action is always added to the top of the list, and thus, performed first when the double-click workflow runs.

On the other hand, Copy as File is performed last, so you can have a double-click workflow where you crop, resize and annotate a shot, and after that, that newly edited shot is copied.

Let’s go over the list of available actions.

Some of these actions are only available when image shots are double-clicked:

– Reduce image resolution

– Annotate Shot

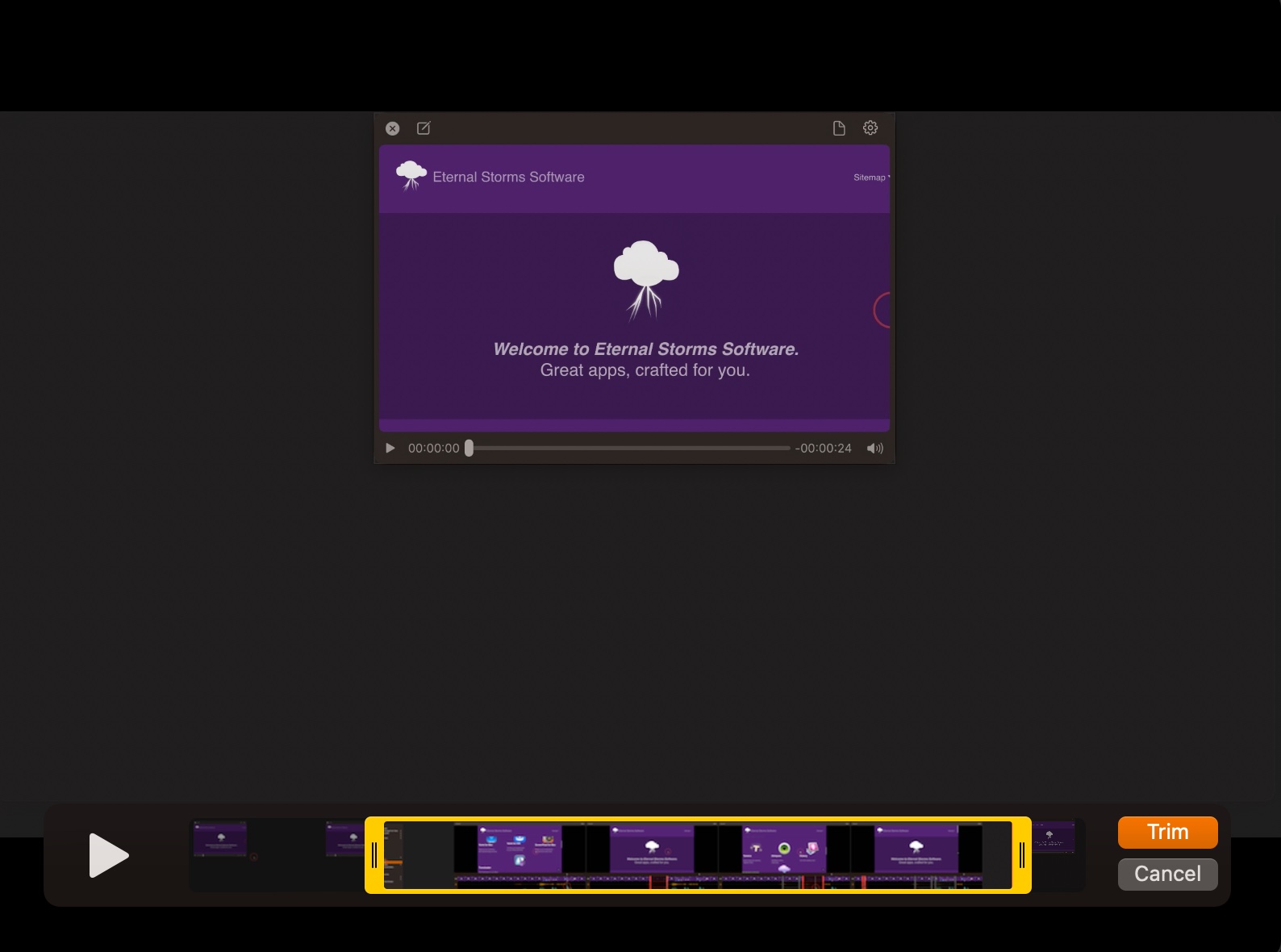

while others are only available for screen recordings:

– Copy Still Image from Video

– Trim Video

– Cut Video

– Remove Audio (All, System, Mic)

Let’s go over some that might need further explanation:

Copy Clicked Text (Additive)

When you double-click a text line in a shot with this active, that text line gets copied.

Double-click another in the same shot, and it gets added to the previous copy.

Copy Still Image from Video

Copies the currently displayed frame in a floating video shot.

Open Copy With

Allows you to specify two apps: one for image shots, and one for video shots.

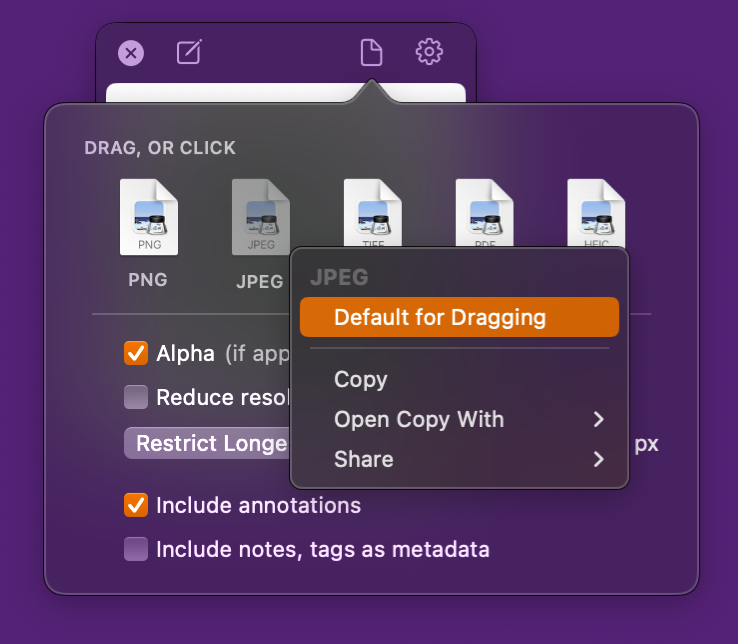

Export to Folder

Lets you select a folder on your disk to save the double-clicked shot to in its native PNG format right away.

Run AppleScript

Run an AppleScript with a copy of the double-clicked shot. Read instructions here.

Run Shortcut

Run a Siri Shortcut with a copy of the double-clicked shot.

Resize Shot

Allows you to specify a percentage to resize to (25%, 50%, 75%, 125%, 150%, 175%, 200%), or to resize it manually.

Rotate

Rotate the shot clockwise, or counterclockwise.

Rate Shot

Specify a rating to give the shot when double-clicking it (from no rating to 1-5 stars).

Add to Folder

Specify a folder the shot should be added to, or let the double-click show the folders menu so you can select one on the fly.

Add Tag

Specify a tag to tag the double-clicked shot with, or show the Tags menu to select one on the fly.

Toggle Opacity Between 100% and

Select an opacity level all the way down to 40% to toggle between with a double-click.

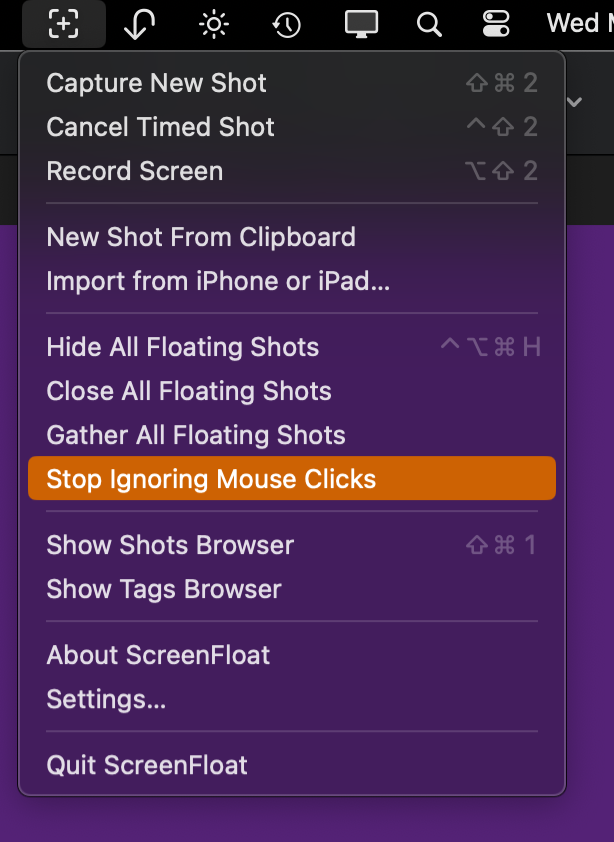

Ignore Mouse Clicks

Makes the double-clicked shot ignore mouse clicks until reverted.

Toggle Visibility Between Everywhere and

Select “Current Space” or “Currently Active App” as an option. Double-click to set it to, say, Currently Active App, then double-click it again to toggle it back to Everywhere.

Resize Floating Shot Window

Allows you to resize the floating shot window down or up in increments, or reset it to 100%.

Some actions are mutually exclusive. For instance, you can’t have both Copy All Detected Text and Copy Clicked Text in one and the same action, because one would override the other, and only the last operation would “take”.

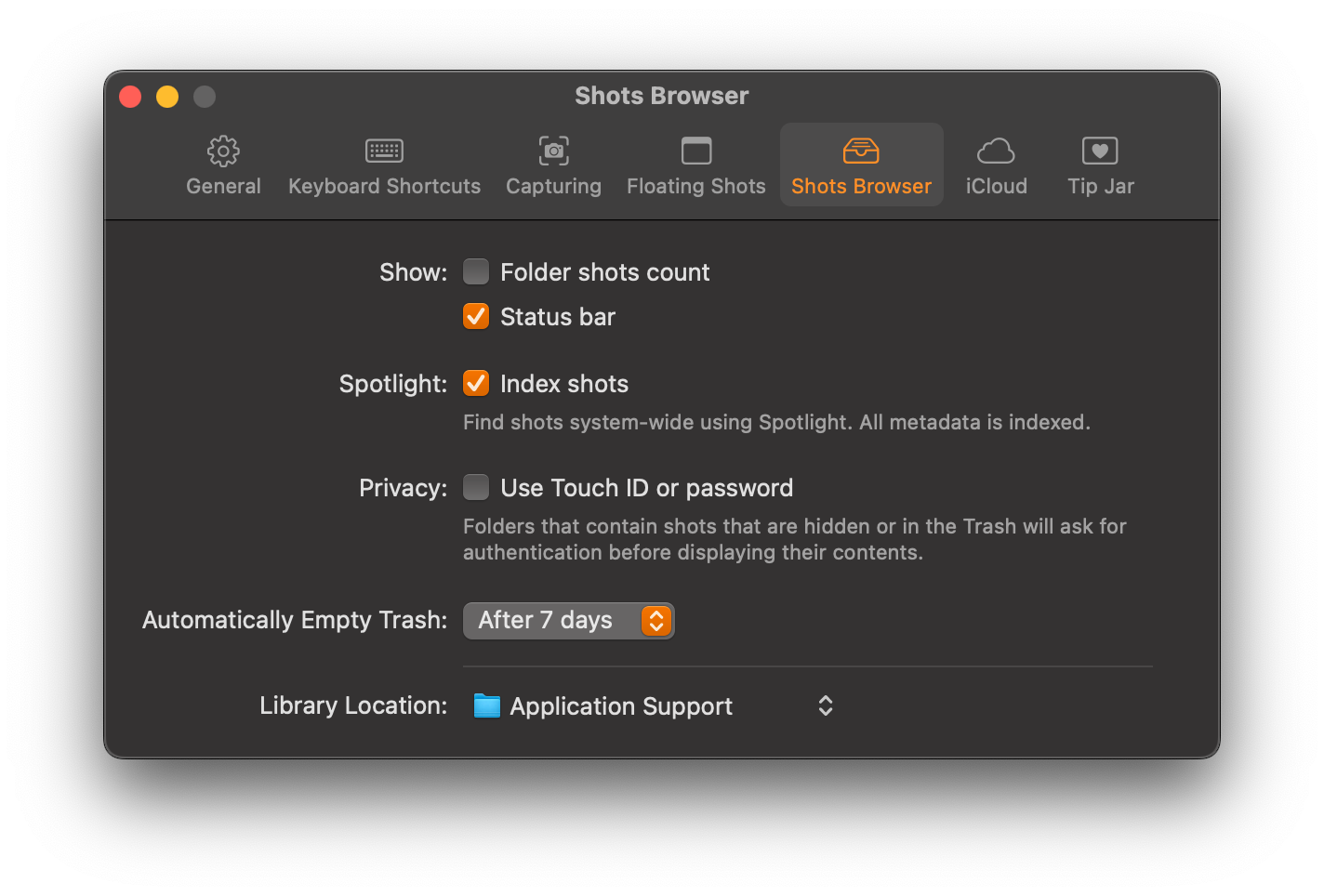

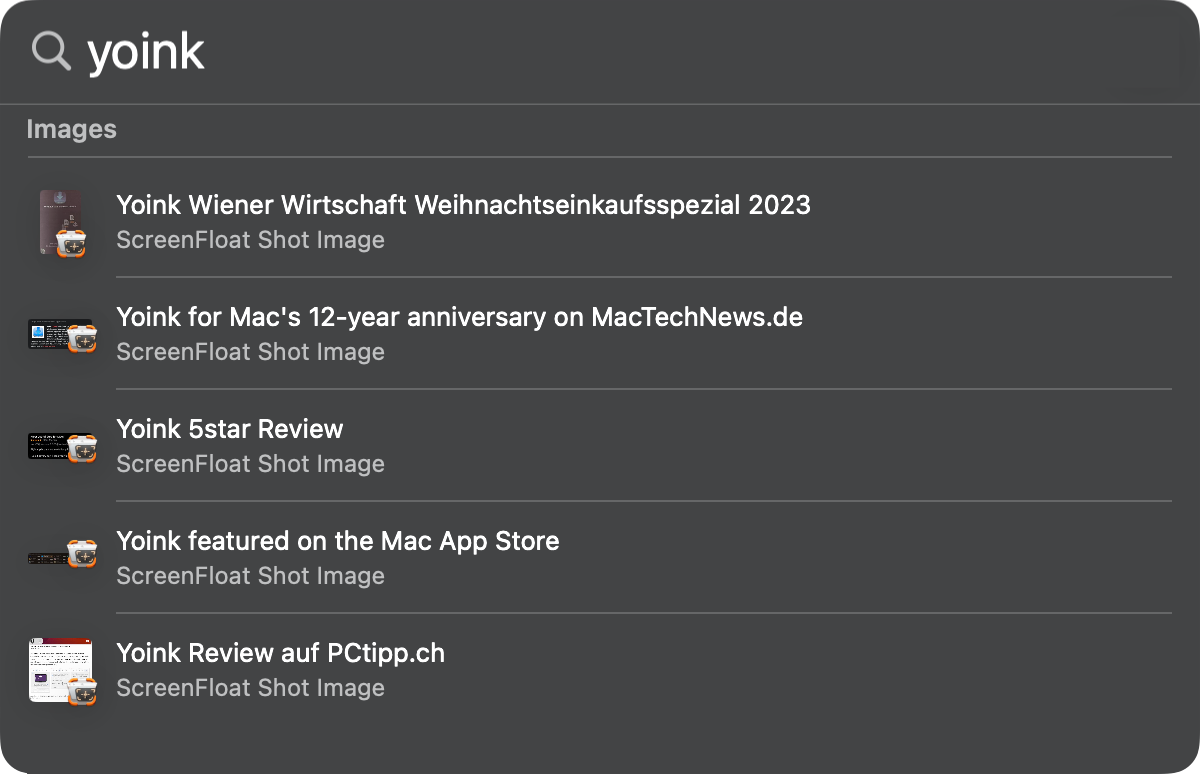

Spotlight

ScreenFloat optionally indexes your shots and their metadata with Spotlight, so you can find them system-wide.

The neat thing about this is that it not only allows you to search by shots’ metadata (title, notes, tags), but also their detected text/barcode content, as well as any text annotations you have made.

Selecting a search result reveals it in your Shots Browser, where a double-click onto it, or the enter/return key on your keyboard will float it right away if you like.

Application Services

ScreenFloat comes with a couple of system services that make it easier to import and float image or video files, even text, or extract still images from videos.

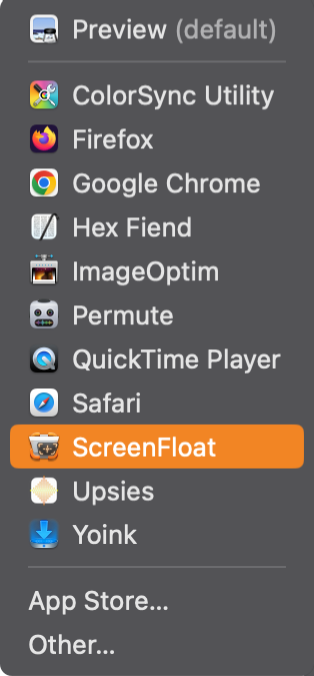

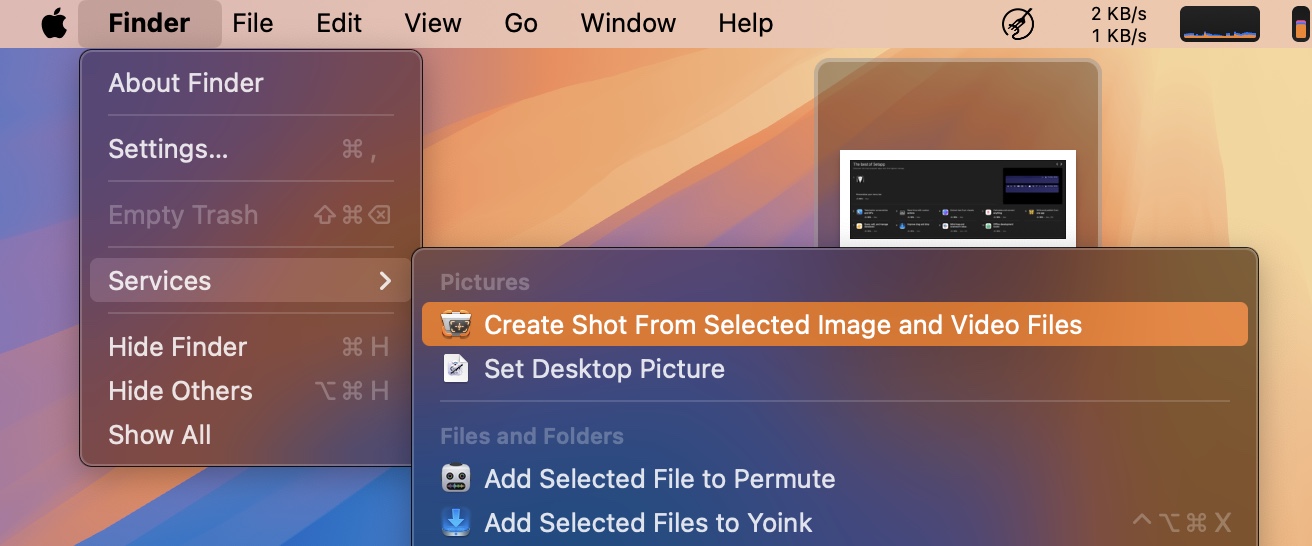

Float Image/Video File from Finder

To float an image or video file in ScreenFloat (and import it along the way), select the file(s) in Finder, then select Finder > Services > Create Shot From Selected Image and Video Files in your menu bar.

Create a Floating Shot from Selected Text

Quickly make a floating note of some text with ScreenFloat – select the text and select Services > Create Shot from Selected Text in the application’s app menu.

(By the way, you can also do this for text copied to your clipboard from ScreenFloat’s menu bar icon.)

Extract Still Images from Movies playing in QuickTime Player

It’s easy enough to just take a screenshot of the player window with ScreenFloat to capture a still image of the playing video, but it’s even easier with ScreenFloat’s service. Select QuickTime Player > Services > Extract Still Image From QuickTime Player Movie and ScreenFloat will create a still image of the playing movie at the current playback position.

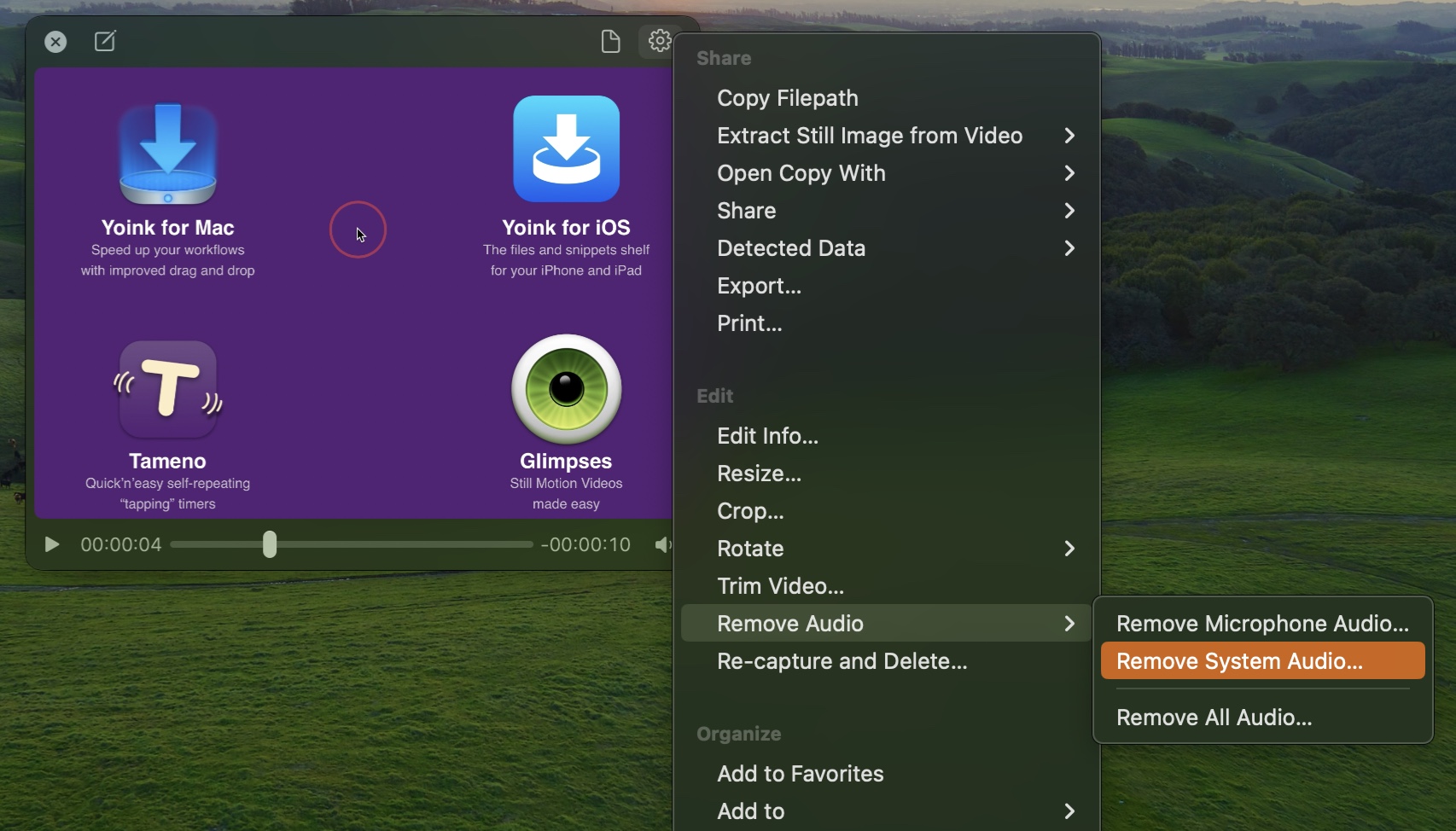

Capture menus and submenus

Capturing a menu and its submenus on its own has become increasingly difficult – perhaps even impossible – with the more recent versions of macOS. It’s very tricky to capture the menu itself without its host window.

ScreenFloat offers a system-wide service that allows you to capture a menu and its submenus in its entirety, or just specific submenus, when you don’t need the entire hierarchy.

Note on how it works: After you select the service “Capture Contextual menu…”, ScreenFloat will wait 10 seconds for a menu to appear (if there’s no menu after 10 seconds, ScreenFloat will cancel the capture). Once a menu appears, you have 3 seconds to navigate to the next submenu, and then again 3 seconds to navigate to the next submenu, and so on. After 3 seconds of no change in menus, the capture will be made.

That’s a Wrap

Whew, what a journey. Congratulations, you now know everything there is to know about ScreenFloat – you can now get the most out of it, I’m sure!

Consider these posts living documents that I’ll keep up-to-date with the changes made to the app, so you’ll always know where to go if something’s unclear.

Speaking of unclear, if you have any feedback or questions, please do not hesitate to write me – I’d love to hear from you.

Links

ScreenFloat Website (+ free trial)

ScreenFloat on the Mac App Store (one-time purchase, free for existing customers)

ScreenFloat Usage Tips

Eternal Storms Software Productivity Apps Bundle (Yoink, ScreenFloat and Transloader at ~25% off)

Contact & Connect

Thank you for your time. I do hope you enjoy ScreenFloat!