[Note: This is a guest blog post written by Thomas Zoechling (@weichsel on twitter), a macOS developer based in Austria, about his Mac app Claquette]

Animated GIF is not a good video format.

Actually it even isn’t a proper video format because it lacks random access and audio support. Nonetheless animated GIFs experienced a rennaisance in recent years.

My theory is, that the format’s success doesn’t stem from the features it has, but from the ones it lacks:

- No random access: Defaults to autoplay – No playback interaction needed

- No sound: Guarantees silence – Always “Safe for Work”

- No support for 32bit colors: Moderate file sizes and a characteristic look

Given those constraints, GIFs are a great way to communicate simple concepts or interactions.

Want to showcase an animation or an application feature? Instead of a static screenshot with paragraphs of text, a 3 second GIF works equally well and also draws more attention.

In my daily life as software developer, I often need a quick way to capture graphical bugs. Those clips can be easily shared with colleagues or included with bug reports.

Sometimes it’s also simpler to attach a GIF to customer support requests instead of explaining how a certain feature works.

To cover my own needs, I wrote a small macOS application that allows me to record the screen and export the result as animated GIF. The app uses a custom recording codec and also covers the rest of the GIF creation workflow like crop, trim and file size optimization.

You can download Claquette from the Mac App Store. For detailed product information, please visit our website.

Development

When I started to implement the Animated GIF feature for Claquette, I began with a naïve approach.

Armed with several years of experience in writing Objective-C and some knowledge about video APIs on the Mac, I wrote a small prototype.

That first version just read a video file frame by frame and sent the resulting frames to ImageIO. ImageIO is a system framework that supports reading and writing several file formats.

It also comes with a basic Animated GIF encoder and so I decided to skip any third party libraries and just use the built-in mechanisms of macOS.

I was able to come up with a working prototype in a single afternoon. The program was just a simple command line utility, but it was able to turn an arbitrary video file into an animated GIF.

There was just one problem… Or actually there were several of them: Due to the inner workings of ImageIO, the program used vast amounts of memory. Also, the encoding took very long and the files it created were huge. On top of all that, the resulting GIFs looked horrible.

So while it only took me one Sunday afternoon to create a working prototype, it took me several months to fix the above issues. Especially the large file size and the bad visual appearance of the resulting GIFs required a lot of research.

Getting the most out of a 30 year old file format

The original GIF specification (GIF87a) was written in 1987 – almost 30 years ago. Animation features were added in GIF89a, which is still the most recent version of the format.

So how is it possible that a file format designed for low resolution screens and 256 colors is still in use today?

It turns out that the GIF specification contains some sections that open room for exploitation. Additionally, the visual nature of GIFs allows for optimizations to trick human color perception.

The format is simple and has the following basic structure:

- Header

- Logical Screen Descriptor

- Global Color Table

- Graphic Control Extension (Frame #1)

– Delay

– Disposal Method

– Local Color Table

– Image Descriptor

– Image Data

- Graphic Control Extensions (Frame #2)

- Graphic Control Extension (Frame #3)

- … (1 GCE for each animation frame)

- Trailer

Header and Trailer are basically just magic numbers that mark the start and the end of the file. The Logical Screen Descriptor contains some general image information like width, height and background color. The Global Color Table is a simple list of colors that may contain a maximum of 256 entries.

Main image information is stored in one or more Graphic Control Extension blocks.

Color Table Generation

The color table sections of the format specification are a good starting point to optimize the visual quality of an animated GIF.

Both palettes are restricted by the format’s infamous 256 color limit. When reducing an image that uses 32bit (16.777.216 colors, 256 alpha values) to 8bit (255 colors, 1 alpha bit) it becomes really important which colors you leave out. The process of reducing large palettes to small ones is called Color Quantization. Choosing a good quantization algorithm is crucial when aiming for visually similar images with a reduced palette.

Naïve quantization implementations are based on occurrence, where seldom used colors are left out in the final image. More elaborate algorithms use techniques like dimensional clustering or tree partitioning.

When developing for Apple devices there are several libraries that provide color quantization functionality. macOS and iOS even have basic color quantization algorithms built-in. Apple’s implementation is part of the ImageIO framework’s CGImageDestination API.

The following sample images were created using different quantization techniques. They illustrate the quality impact of the used algorithm on the final image.

The first image shows the output of CGImageDestination. The resulting colors are noticeably off. Apple’s encoder also messes up the transparency color in the GIF palette, which leads to holes in some areas of the image (e.g. the titlebar).

The open source library FFmpeg also includes a color quantizer. FFmpeg produces way better results than CGImageDestination. The colors are more vibrant and the transparency color is set correctly.

The color quantization library used by Claquette also outputs a good choice of colors. Additionally the app performs color matching to avoid color shifts and to guarantee correct gamma values.

Frame Difference Calculation

Another important factor during GIF generation is efficient frame difference calculation.

The disposal mode in the Graphic Control Extension allows an encoder to specify how the context is set up before the next frame gets rendered.

GIF89a defines 4 disposal modes:

- Unspecified: Replaces the existing canvas with the full contents of the current frame.

- Do not Dispose: Leaves the existing canvas as-is and composites the current (sub)frame over it.

- Restore to Background: Sets a defined background color and draws the current frame. Areas outside of the subsection in the Image Descriptor shine through.

- Restore to Previous: Fully restores the canvas to the last frame that did not specify a disposal method.

The Image Descriptor section can be used to define a sub-image which does not provide pixel data for a full frame. Instead it contains coordinates and pixel data for a subsection of the full image.

By using frame differences and sub-images with a proper disposal mode, redundant image data can be avoided. Depending on the nature of the input video, this can greatly reduce the file size of the final GIF.

Modern video codecs like H.264 use techniques like macro blocks and motion compensation. Those methods introduce small errors that propagate from frame to frame. Propagated errors show up as noise when calculating frame diffs and eventually lead to unnecessary large files.

Claquette uses a custom lossless codec, that only stores regions that actually changed. This guarantees exact frame diffs.

The following images show the difference between frame #1 and frame #2 of a screen recording. The only effective change between those frames is a change in the mouse cursor location. An exact diff should therefore only contain an offsetted cursor image.

The above diff image was created between 2 frames of an H.264 encoded movie. The visible noise is a result of intra-frame encoding errors.

The second image was created by Claquette’s image diff algorithm. It only contains the mouse cursor – The only image element that actually changed between frame #1 and #2.

Finishing Touches

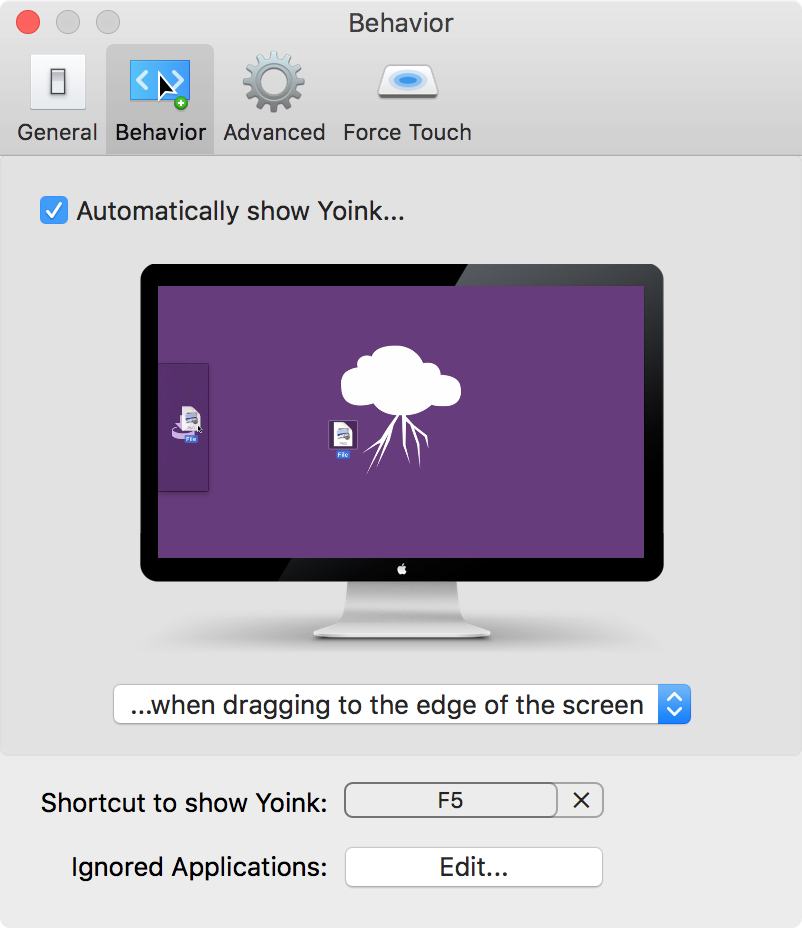

After implementing technical details like encoding and optimization, there were still some features missing. Claquette needed an editing UI to handle the whole GIF creation workflow.

As I wanted to keep the app lightweight and simple to use, I decided to add only a small set of editing capabilities: Trim and Crop.

Claquette uses AVFoundation, and therefore I was able to use the AVPlayer class, which comes with a built-in trim tool.

Crop functionality was a bit harder to implement. AVFoundation doesn’t provide any UI component to display crop handles so I had to implement my own.

Besides the standard drag & move interface, my implementation also provides some unique features. It offers alignment guides with haptic feedback and the possibility to enter crop coordinates.

You can see the final implementation of the crop utility in the animated GIF below:

Launch

To launch the animated GIF feature, I prepared a press kit and wrote mails to review sites that mostly cover Mac software.

Additionally I submitted the app to Product Hunt and informed Apple’s App Store Marketing team.

I can really recommend to launch on Product Hunt: Claquette received over 400 upvotes and finished in the top 3 on launch day. The site also hosts a friendly community, that makes extensive use of the Q&A section below each hunted product.

I was also lucky to get some mentions from high profile Twitter users and good App Store reviews.

Two weeks after launch, Apple suddenly moved Claquette into the “New and Noteworthy” feature section on the Mac App Store front page. Of course this also lead to a noticeable spike in the sales charts.

Overall I was very pleased with the release and the reception of Claquette 1.5.

—

Thomas Zoechling is an independent software developer living in Vienna, Austria.

Besides working on his own products, he is also doing contract work. Currently he is helping IdeasOnCanvas to develop the excellent mind mapping software MindNode (macOS, iOS).