Having implemented the backend and licensing mechanism, there was still an important part missing: a way to download and install updates for the app.

A “safer” download

My app trial downloads have always been just a direct file download. But because I wanted the auto-updating mechanism in my app to use that same download path, I needed to add a little layer of validation/safe-guard there.

Step 1: sign the zip file cryptographically with a private key, and upload the signature data alongside the zip file.

Step 2: write a download PHP script. Instead of just initiating a direct file download, the script starts the download, only if the zip file’s signature could be verified with the public key. If there’s a signature mismatch, an email is sent to me so I know there’s something going on.

Step 3: implement the download and signature check in the app. The app downloads the update zip file using the PHP script, with the signature of it passed along as a header. That allows the app to verify the zip file’s signature with the public key, before unzipping it. If the signature can’t be verified (because it was tampered with, or the download got corrupted somehow), the zip file is discarded and an error presented.

I got you, “gotcha”s

With the PHP download script, I encountered two “gotcha”s.

One was that, no matter what I tried, I couldn’t set the Content-Length header, which lets the downloading client know how much data to expect (so a download progress can be displayed properly). A lot of googling later (I also tried ChatGPT for fun, but it was no help here), there’s an environment variable that needed to be set on my server:

SetEnv ap_trust_cgilike_cl 1

With that, it miraculously started working.

The second “gotcha” was resumable downloads.

For a file that is only a few megabytes, it’s not that big of a deal, but for larger downloads, it is convenient and responsible to have resumable downloads.

If a download halts because of, say, a loss of connection, the downloader is able to later pick up the download from where it left off, instead of discarding what it had already downloaded and having to start over.

It took a bit of trial and error, but thankfully, there are lots of code samples for this available, this one being a prime specimen, and I eventually got it working.

Release the Notes

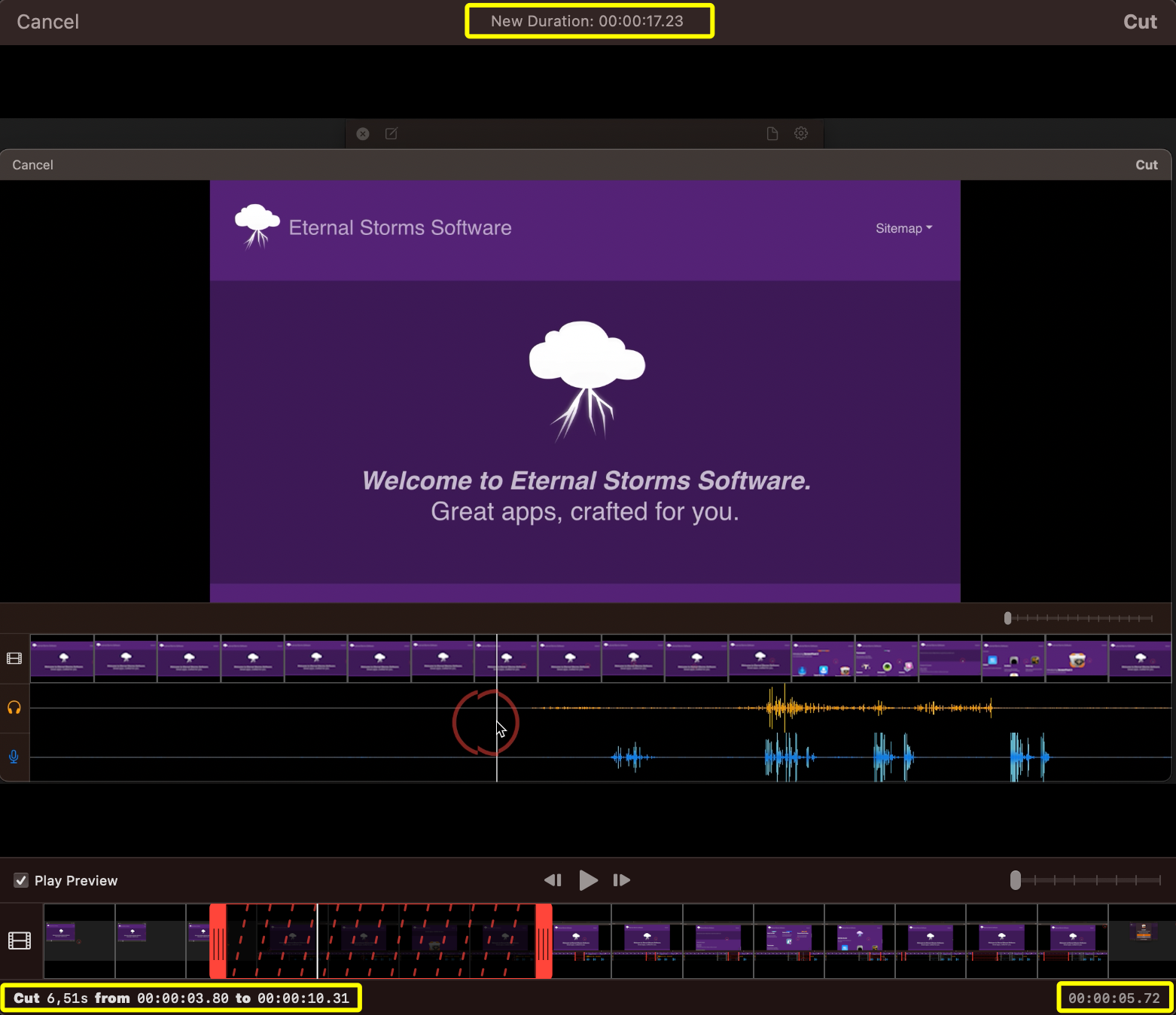

I just recently revamped my release notes to be more interactive:

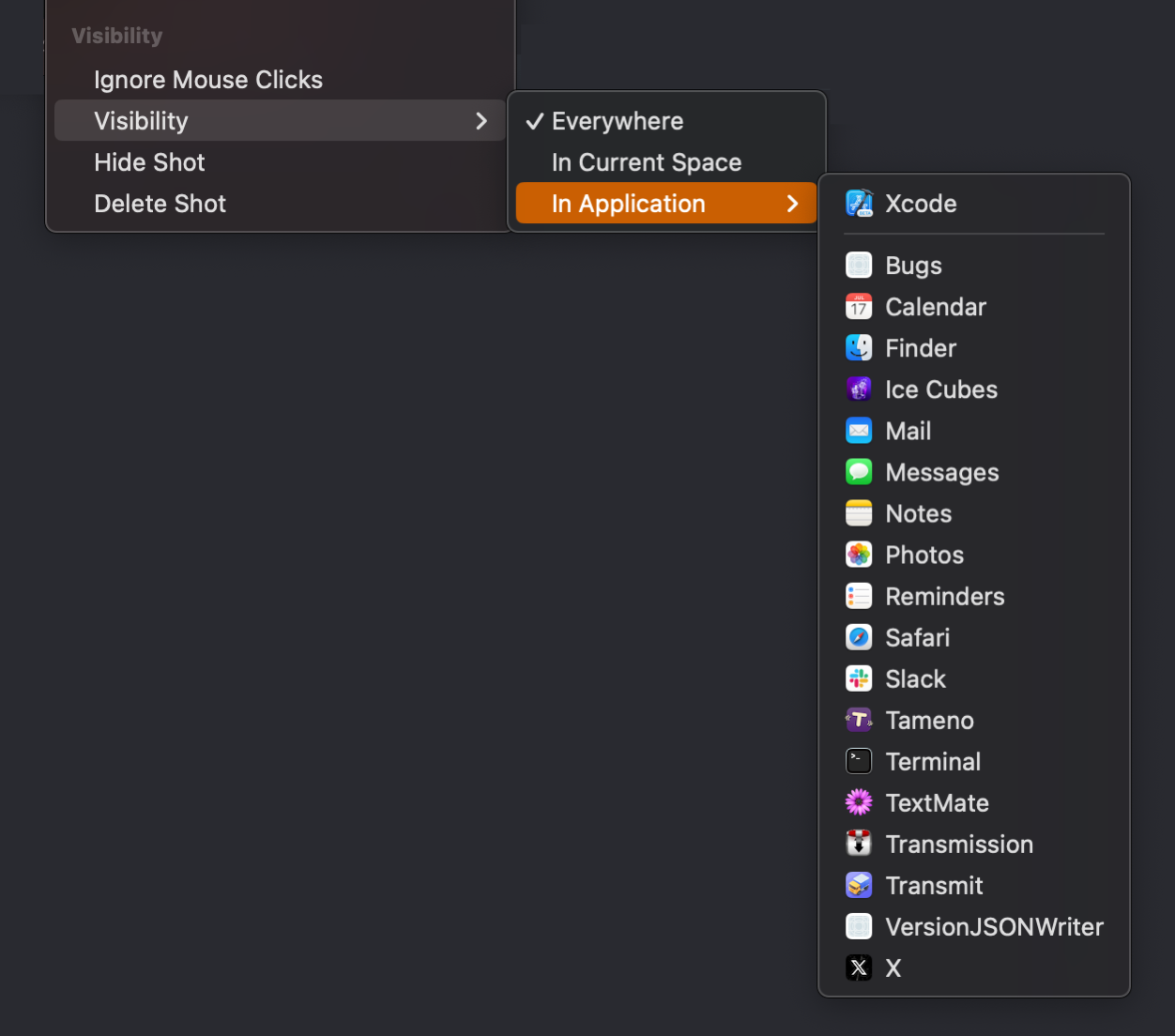

It gives a nice overview of new features, improvements and bug fixes, I can display a nice header or footer if I like, and I can show users new features in action on-the-fly as a video, an image, display a website for instructions, or take users to features or settings in-app right away.

But I hadn’t thought it through enough. All this had been powered by a single JSON file. For multiple releases, over the years, that file would become larger and larger. And to display information for one release, I’d have to download the entire file. So I had to go back in and change that.

Instead of a single JSON file, I now have it in a database, each release in a row, so I can obtain information for individual releases, instead of having to download all of them at once.

Interacting with this database is powered by a custom PHP API.

It lets me retrieve all version strings for an app, alongside their release dates and build numbers – crucial for self-updating.

I can then request an individual release’s information as an on-demand created JSON. I use this in the Mac App Store version to show what’s new after an update has happened, and in the non-Mac-App-Store version to display what’s new before an update.

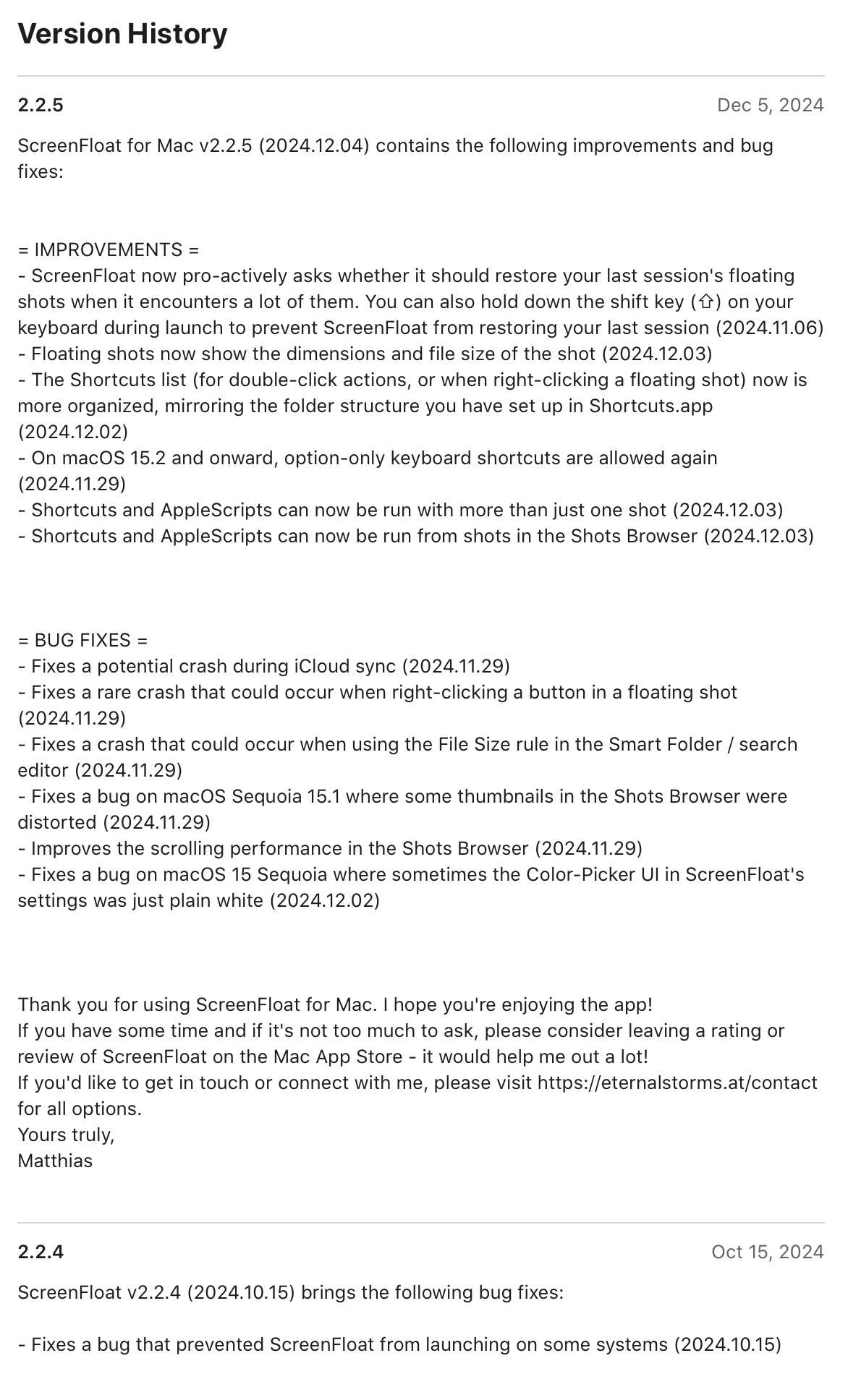

Additionally, it can return more than one row of releases. That allows me to show multiple releases in the “Update available” screen:

Say a user is on version 2.1. Versions 2.1.1 and 2.2 have already been released, but the user never updated to them. Now version 2.2.1 is out, and the user gets notified. Not only does the update dialog show what’s new in version 2.2.1, users can also see what was new in v2.2 and v2.1.1. Yay.

For feeding information into the database, I wrote a little PHP web “app”:

I can add localized release notes for a feature, improvement or bug fix, and manipulate the JSON (on the right side) directly, too, if I need to change the order, or fix a typo. I can go back into any version, any time, in an organized manner.

Lastly, I can download a nicely-formatted .txt file for each localization I can copy-paste into the App Store’s What’s New section (or anywhere else I like):

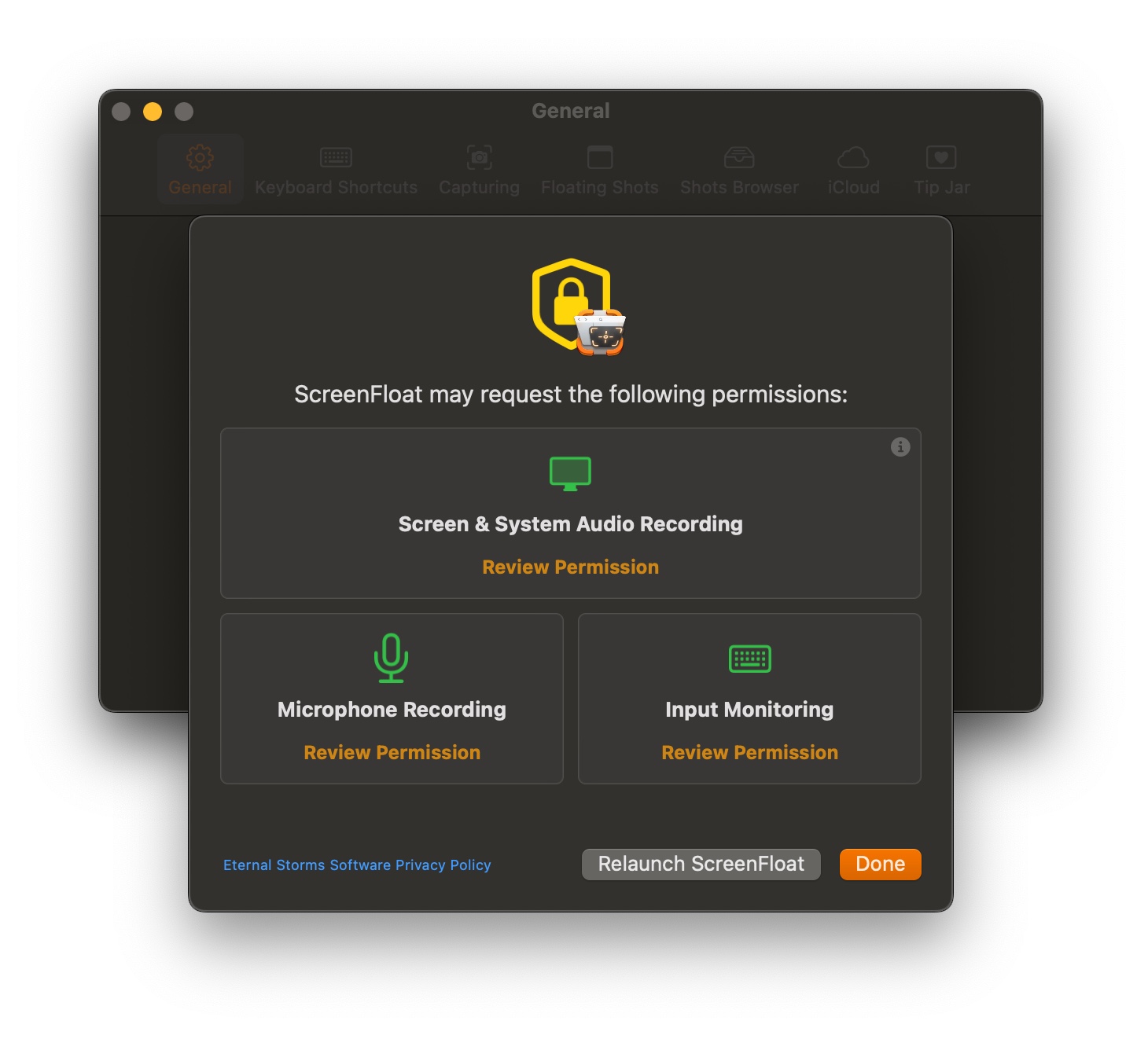

Self-Updating App

The simple and sane thing to do would have been to go with Sparkle. It’s fantastic. It can work with zips and other compression formats, dmgs, can do diff updates and all that stuff. It’s really good, and if you need any of that, or just want an easy way to do updates, save yourself the headache and just use Sparkle.

All I needed, though, was to unpack a zip file and install that update. And with all that custom code I wrote on the backend, to perfectly integrate and take advantage of it all, I figured I’d write my own updating mechanism.

The app has to:

1) Check if a new version is available

2) Display to the user what’s new and ask whether they’d like to download the update

3) Download the update

4) Verify the zip file’s signature

5) Unzip the zip file if the signature is okay

6) Verify that the new bundle is code signed, and that the code signature’s team of the new bundle is the same as the old one’s

7) Replace the old copy with the new one

8) Relaunch

Items 1 through 4 were easily done – all the heavy lifting is already taken care of by the server.

Item 5 – unzipping – is where it began to become tricky.

Actually, it already became tricky zipping up the app in the first place.

Like I stated before, I upload a zip file and its signature. To create both, I use a Shortcuts.app shortcut – I select the app produced by Xcode, it gets zipped up, a signature file is created, and I manually upload both to my server.

Alas, the “Make Archive” shortcut is teh suckage when it comes to apps.

Try it yourself: Create a “Make Archive” shortcut that creates a zip archive from an app, then unzip that archive and double-click – it won’t work (or, even worse, it’ll work on your Mac, but on a different one, it won’t. Thanks to UTM, I was able to figure that out).

So instead, I use a Run shell script phase with the ditto CLI:

ditto -ckX --sequesterRsrc --keepParent <app-file-path> <zip-file-path>

Unzipping that and running the app worked right away both on my Mac and in the UTM virtual machine, so the first hurdle had been taken.

Unzipping, then, in the app, also had to be done using that CLI:

ditto -xk <zip-file-path> <unzip-file-path>

Because I didn’t test each step right away and implemented the flow in one go, when I first tried it, I wondered where my mistake was when the app didn’t launch. It was only after quite a bit of backtracking and research that I came to the conclusion that my way of zipping and unzipping was the culprit.

My current iteration of my self-updating mechanism isn’t complete yet.

It can update itself when the user account that first installed the app is also the one updating it. But if a different user account runs the update, it fails, because of insufficient privileges. I had one implementation where it worked once, and then nobody could update anymore – yikes. I had another implementation where, when replacing the old app with the new one, for some reason the /Contents/MacOS/ folder could not be replaced (but the files in MacOS were deleted), corrupting both the old and the new copy.

Let’s just say, I hit some weird edge cases here.

This is obviously something I’m working on still, but in the meantime, when I suspect it’s a different user account attempting the update, I present the user with the new version of my app in Finder, and show instructions on how to manually update.

It’s nowhere near a perfect user experience yet, but it was a trade-off I was willing to accept for the time being (on behalf of the user, I’m afraid), knowing the upside of having control over the entire thing and eventually figuring it out.

It’s my main drive at work – figuring stuff out.

Next Time

Next time, I’ll talk about how and if it all worked out. I hope to see you then!