[Note: This is a guest blog post written by Martin Nguyen (@iMaddin on twitter), an OS X- and iOS developer based in Austria, about his Mac app Gestimer]

I don’t like to keep too many thoughts in my head at the same time. Also, my short-term memory isn’t the greatest. If I had to cook dinner and then went back to my Mac to continue whatever I was working on, I’d probably forget about my dinner.

That’s especially true while coding where I have to be completely focused. Other unrelated thoughts are too distracting when writing code. I feel comfortable knowing that an app will take care of such thoughts as its memory is most likely better than mine.

Not too long ago – while I was at university – I noticed that todo apps weren’t entirely fitting all my needs. Sometimes I had these little tasks like reminding me to make dinner (because I’d forget and be too busy or focused with other things) or that I had to leave for a lecture in half an hour. It was too much of a hassle to set alerts for those tasks that have a short lifespan. To me it just feels slow to enter numbers with a keyboard for inputing dates and times, especially without a num pad.

As the type person who sits at my Mac most of the time, I decided to make a Mac app to work around this problem. After a couple of months and failed attempts at such an app, the idea that later became Gestimer popped into my mind: “Wouldn’t it be great if I could just drag down from the menu bar to create a quick reminder?” This seemed so simple and fast. It was the perfect solution.

Development

With this idea in my mind and a few sketches in my notebook, it was time for the execution. This was back in 2012 when I had just begun learning to code. As every beginner knows, coding is frustrating. Everything can break easily and you have no clue why. Objective-C was also not the easiest thing to learn without any prior programming knowledge. Additionally, making Mac apps appeared to be much more difficult than making iOS apps.

I shelved the project. There was nothing that was anywhere close to Gestimer out there so it was impossible finding resources that would help me realize the app.

With iOS 7, Apple introduced UIKit Dynamics. It seemed like a fun way to make interactions so I played around with it. I noticed that UIKit Dynamics allowed me to easily do something close to what I had in mind. It was only available for iOS and not OS X but it still allowed me to produce a version of Gestimer, even if it wasn’t in the intended environment. Here is the iOS version which was available from 2013 to 2014:

Gestimer for iOS didn’t do too well but that’s okay. I didn’t do any marketing as I simply put it up on the App Store and I was already happy to have an app that I made and used every day. Creating the iOS version taught me a lot and as I learned from more projects over the last couple years, I felt comfortable enough to tackle the Mac version again. I was especially motivated by the announcement and release of Swift.

I made some good progress on Gestimer for the Mac during the summer of 2014. The idea never changed: drag & drop from the menu bar to create a reminder. I worked on the app on and off, whenever I felt like it, whenever I slept off the frustration and head-scratching of the previous day.

As there was no UIKit Dynamics for the Mac, it was a lot more difficult to imitate the iOS version and to get things behaving as intended. By late 2014 I had a rough but useable version. I was never in a rush to release Gestimer. In fact, I stopped working on it for a couple months after that. I was again content with having an app I made and used every day. It also gave me time to simply use the app and think about if it truly did the things well that I wanted it to do.

If you haven’t seen Gestimer yet, have a look at a short clip here.

https://vine.co/v/ehEwHbWKhUj/embed/simple

Marketing

Sometime around mid-April 2015 I started sharing a beta of Gestimer with people who I thought might be interested. Besides gathering feedback, it got me excited about the prospect of launching and hear what even more people will say about it. That’s where I decided to do some proper marketing. I won’t go into detail about this here as it would double the size of this post but I took marketing very seriously.

The basic outline of what I had:

– a short 10s clip of the interaction on the website

– collected email addresses for launch day

– made a YouTube video (currently over 50k views)

– a nice press kit

– localized Gestimer into 9 languages (now even more!)

Launch

There was little press coverage on launch day, but I had Gestimer up on Product Hunt thanks to Matthias who kindly sent me an invite. Someone had also posted the app to Hacker News. Both sites led to a lot of traffic. At the end of the day Gestimer was sitting on the 3rd spot on Product Hunt. To this date, the PH submission for the app has received over 400 upvotes. Twitter also helped a bit, though I believe people overestimate its effectiveness.

More press coverage followed and an increasing number of people spread the word. During launch week Gestimer reached the #1 spot in the Top Paid charts on the Mac App Store in multiple countries including the US, UK, and Germany. While sales numbers on the Mac App Store are small compared to the iOS App Store – even if you reach the top charts – it’s still been good. It’s nothing to complain about.

The reception for Gestimer has been overwhelming and I would have never imagined it becoming this successful. It makes me very proud to have done all the design, code, and marketing work on my own.

If you’d like, you can find out more about Gestimer here.

——

Martin Nguyen (@iMaddin on twitter) sometimes works on iOS and OS X apps and lives in Austria. While he enjoys coding, he is still trying to figure out the next step in his life.

![]() Yoink

Yoink ScreenFloat

ScreenFloat![]() Transloader

Transloader![]() Glimpses

Glimpses

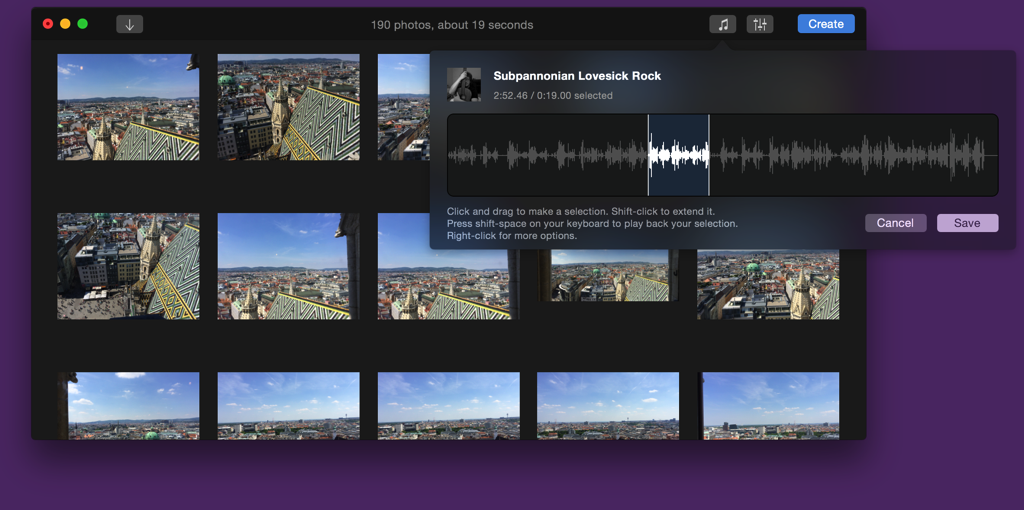

A still from a video created with Briefly 1.5.2 (top) compared to the same video created with Glimpses 2.0 (below)

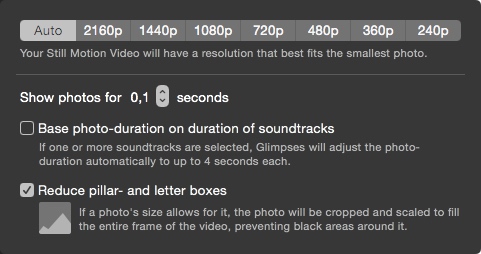

A still from a video created with Briefly 1.5.2 (top) compared to the same video created with Glimpses 2.0 (below) Glimpses Video Settings

Glimpses Video Settings